Everything You Need to Know About Aridity and Passive Purification

Aridity | from the Latin aridita: dryness, drought, meagerness; dullness, flatness.

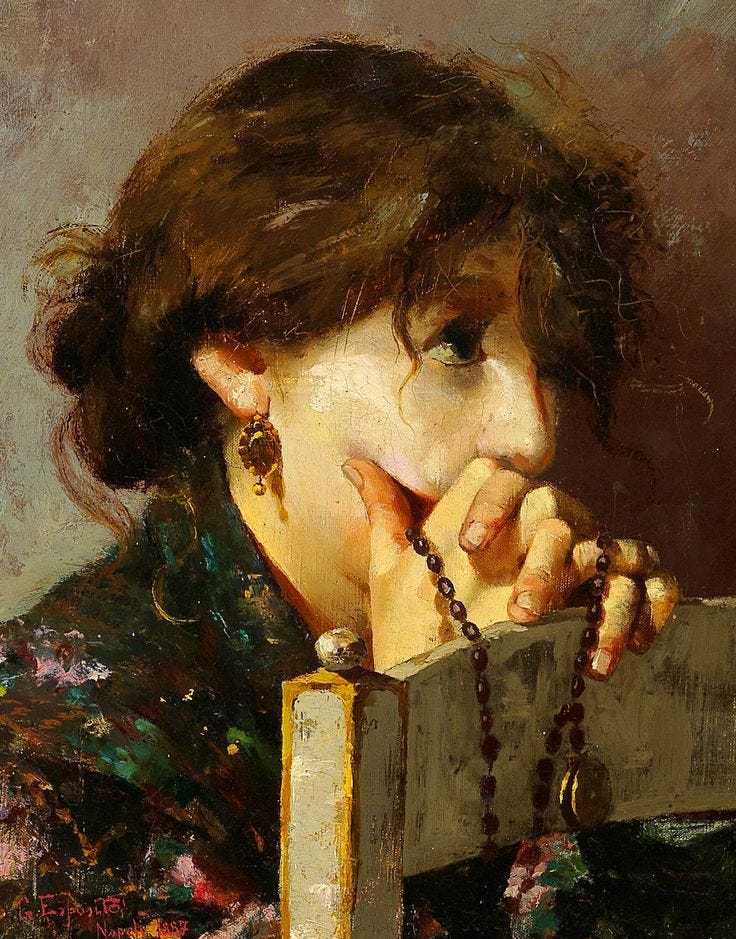

"The greatest pain of souls in meditation is to find themselves sometimes without a feeling of devotion, weary of it, and without any sensible desire of loving God; and with this is joined the fear of being in the wrath of God through their sins, on account of which the Lord has abandoned them; and being in this gloomy darkness, they know not how to escape from it, it seeming to them that every way is closed against them." - St. Alphonsus Ligouri

The first time a state of aridity descended upon me, I was thoroughly confused. I had never been taught about this condition in the spiritual life - a condition which is very normal in the life of a Christian - and not knowing what it was, I thought there was something wrong with me. Prior to this onset of dryness, my prayers were filled with sweet consolations, but then it felt as though the light had been extinguished and I was abandoned by God. It was startling and unexpected, to say the least.

The writings of St. John of the Cross revealed to me that my experiences were not only normal but also necessary. I discovered that aridity is a common topic among theologians, spiritual writers, saints, and in all works of ascetical theology and spiritual literature, because at some point, every soul will encounter it as a standard part of spiritual growth

For a few years now I’ve been collecting various writings and meditations on aridities, and I have decided to put them together, the best that I can, in some kind of coherent whole, for the purpose of helping others who find themselves languishing in this dry desert.

In this article, you will find an explanation of what aridity is, why it happens, how to cope with it, and you will discover that, when facing the trials of aridity, you are in the company of the greatest of saints.

“As [aridities] can be the most distressing of trials, we cannot be too well armed to sustain their assault.” - Dom Vitalis Lehodey, Holy Abandonment

1. Definition of Aridity.

First, let us briefly and simply define aridity. I have reviewed multiple definitions from different sources, and I believe the one provided by Rev. Adolph Tanquerey (1854-1932) encapsulates it most effectively:

"Aridity is a privation of those sensible and spiritual consolations which make prayer and the practice of virtue easy. In spite of oft renewed efforts, one no longer relishes in prayer; one even experiences a sense of weariness; one finds prayer irksome and the time given to it endless; faith and trust seem dormant; once alert and joyous, one lives now in a sort of torpor and acts only by a sheer force of the will."1

He notes: "This is indeed a most painful condition, but not one devoid of advantages."

2. Two Kinds of Aridity

It is important to quickly distinguish between the two kinds of aridity.

There is one that is a purifying dryness which comes from God, but there is another that is caused by our own negligence and lukewarmness.

In other words, a dry time can proceed from our own faults, so we must search ourselves honestly (yet not with anxiety) to determine if we are the responsible cause, by checking if our tendencies consent toward pride, if we have become spiritually slothful, or if we are overly attached to worldly pleasures (for God will not have a divided heart). St. Francis de Sales also points out that withholding anything from our spiritual director would be a deception that would cause God to withhold consolations. And so, if the cause of aridity is determined to be due to self, then one must strive with all humility to remove these obstacles and barriers to God’s grace.

However, for the purpose of this article, I am treating of the first kind only. I am writing this assuming that the aridity experienced by the reader is the purifying kind, imposed by God, and not due to his own tepidity.

3. Signs of Spiritual Aridity

In the Dark Night of the Soul, St. John of the Cross explains the common signs that God is inflicting aridity on a soul:

1. The first sign is: “the soul finds no pleasure or consolation in the things of God, it also fails to find pleasure in anything created.” 2 This is when we find no comfort in the things of God, and none also in created things. For when God brings the soul into the dark night in order to wean it from sweetness and to purge the desire of sense, He does not allow it to find sweetness or comfort anywhere.

2. The second sign is that, in spite of aridity, “the memory is ordinarily centered upon God with painful care and solicitude, fearing that it is not serving God.” 3 The memory dwells upon God with a painful anxiety, fearing that it does not love God and is not serving Him; and at the same time, it continues to seek Him with the anxiety of one who does not succeed in finding its treasure. The soul remains then always occupied with God, although in a negative, painful way, as if suffering because of the absence of a loved one.

3. The third and last sign consists in the fact that “the soul can no longer meditate or reflect in the imaginative sphere of sense as it was wont, however much it may of itself endeavor to do so.” 4 The soul would like to meditate; it applies itself, tries as hard as possible, and still does not succeed. When this state continues, it tends to invade the whole soul in such a way as to make meditation habitually impossible.

4. Purpose of Aridity

Believe it or not, these painful periods of aridity have an important purpose.

Fr. Lehodey explains:

"Both consolations and aridities are designed by God to play a very important part in the sanctification of souls. In their action on the soul, they supplement and correct each other. As a rule, He begins with consolations in order to gain our hearts and support our weakness. When the soul has made some progress, and is strong enough to endure more energetic treatment, He sends her a preponderance of suffering. We have such need to die to ourselves." 5

Aridity can aid us in the following ways:

>Detachment

Tanquerey explains the Providential purpose of Aridity thus: "When God sees fit to visit us with aridity, it is in order to detach us from all created things, even from the happiness derived from devotion, that we may learn to love God for His sake alone." 6

>Humility

God likewise humbles us by showing us that we don't have a right to consolations; they are an entirely free gift. They are His to give when He wills, as much as He wills, to whom He wills. It should humble us to realize how helpless we are without His grace, and how unworthy we are of His gifts.

>Proof of Love

St. Alphonsus Ligouri explains that, as a soul progresses in the spiritual life, it becomes necessary for God to withdraw spiritual consolations so that the soul can prove its love:

"When a soul gives itself up to the spiritual life, the Lord is accustomed to heap consolations upon it, in order to wean it from the pleasures of the world, but afterward, when He sees it more settled in spiritual ways, He draws back His hand, in order to make proof of its love and see whether it serves and loves God unrecompensed with spiritual joys." 7

By aridity and temptation, the Lord proves His lovers.

>Test and Strengthen Faith

Saint Thomas Aquinas didn't specifically use the term "aridity" in his works, but he did address spiritual dryness. He said that such dryness can be a trial sent by God to test and strengthen faith. He explains that such trials can serve to purify the soul and lead it to greater spiritual maturity. 8

>A Source of Suffering for Expiation and Atonement

In a state of aridity we serve God without any enjoyment, so we serve Him on principle and by sheer will-power; thus, we mortify self-love, and this suffering becomes an act of expiation and atonement.

>Perseverance

It teaches us to persevere in prayer, and thus strengthens us in virtue.

>Generosity

It gives us an opportunity to be very generous to God by giving Him our time, love and attention despite the arid feelings.

In essence, then, spiritual aridity is a trial that can effectively helps us grow in virtue and faith, if we know how to use it to our advantage. It is a time of purification and preparation for closer union with God.

5. Our Attitude Toward Aridity

What, then, should our attitude be when we are faced with aridity?

I have extracted from various works to list the most common ways of persevering through aridity:

Be thoroughly convinced that it is more meritorious to serve God in the absence of warm feelings than in the midst of many consolations.

In order to love God, it is enough to will to love Him. In fact, the most perfect act of love consists in conforming our will to God, not in warm fuzzy feelings. Rest assured that you gain much more merit by serving God in a time of empty dryness than you would in a time of sweet consolation. This is because, as Aquinas said, devotion does not consist in feelings, but in the desire and resolution to embrace promptly all that God wills. It is found, rather, in patient and humble submission to the withdrawal of the consolations. Spiritual progress will be seen by a willingness to continue in pious devotions despite the feelings of dryness.

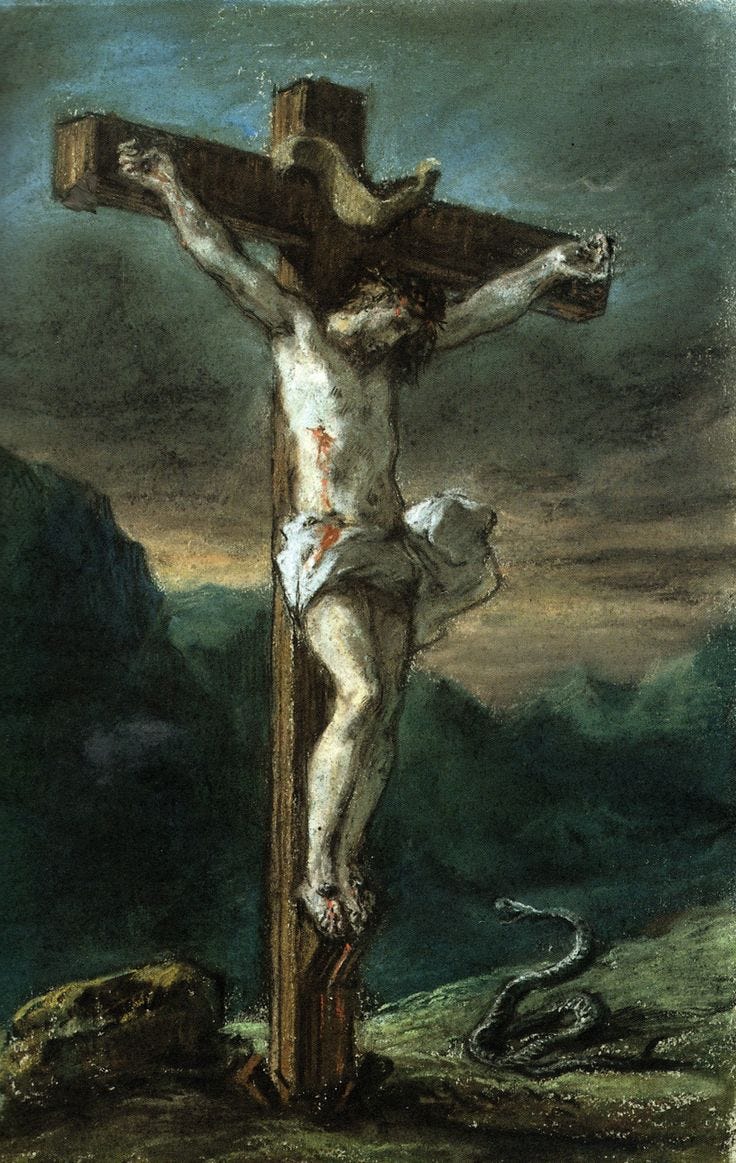

St. Alphonsus Ligouri points out that such was the prayer of Jesus Christ in the Garden of Olives: it was full of aridity and tediousness, but it was the most devout and meritorious prayer that had ever been offered because it consisted in these words: "Not my will, but Thine be done." And Rev. Tanquerey says that we render our acts more meritorious by uniting ourselves to Jesus in the Garden, Who consented to experience sadness and weariness of soul out of love for us.Never lose heart and never subtract anything from your pious exercises, from your good efforts or resolutions, but rather imitate Our Lord, who being in agony, prayed even longer (Luke 22).

Aquinas emphasizes this need for perseverance in prayer even when one does not feel spiritual consolation, trusting that periods of dryness have a purpose in God's plan.

St. Alphonsus warns us: "Some foolish persons, seeing themselves in a state of aridity, think that God may have abandoned them; or, again, that the spiritual life was not made for them; and so they leave off prayer and lose all that they have gained. In order to be a soul of prayer, man must resist with fortitude all temptations to discontinue mental prayer in the time of aridity."

He councils us to "never give up mental prayer in the time of aridity." Even if tediousness assails us, he recommends dividing meditation into several parts and to spend most of the time petitioning God for help. He says to persevere in this even if it appears that we pray without confidence or fruit. It is sufficent to say: "My Jesus, mercy. Lord, have mercy on me."

St. Teresa of Avila encourages us: "Though aridity should last for life, let not the soul give up prayer; the time will come when all will be rewarded."When you are given the grace of a great consolation, don't think too much of receiving them, but stay humble and remember that you are unworthy of such graces, and it can quickly and easily change into the opposite.

Always remember that these trials of aridity are actually profitable to you, and in fact, they are much more profitable than if everything always went your way and felt great. If you can seek to honor and glorify God during times of adversity, then you have an opportunity to show your love by an act of the will, proving that your love is not based on the consolations that you receive. You go to God because of Who He is, not because of what you get from Him. This is a true test of love.

The essential core of prayer is in this act of the will. Piety and devotion are alive in the will, not in feelings. We can pray and exercise virtue even when we feel cold and dry. Devotional acts can exist despite feelings of aridity. Even in times of dryness, we can remain firm in our decision to give ourselves to the service of God. We shouldn't go to prayer with the purpose of pleasing and satisfying ourselves, but only to please God and to learn what His will is. Therefore, whether He sends us consolation or desolation, He deserves to be served the same. Our aim should be to do our duty, regardless of how we feel about it.

Padre Pio challenges us with these wise words: "What does it matter to you whether He wishes to guide you to heaven by way of desert or by the fields, so long as you get there one way or the other? Put away any worrying which results from the trials by which the good God desires to test you."In some cases, the best thing to do is to give oneself up entirely to God. If meditation is impossible, then content yourself with simply directing your attention lovingly and calmly toward God. Keep your soul free of anxiety and be in a state of docility to the Director, trusting in God with a simple and loving gaze.

6. Meditations on Aridity from Fr. Andre Jean-Marie Hamon

Fr. Andre Jean-Marie Hamon wrote a five volume work containing meditations for every day of the year. I pulled from his meditations on aridity to see how we can profit from his explanations and advice. 9

Fr. Hamon opens his meditations on aridity by calling to our mind Our Lord's words in the Gospel to the Apostles: "It is expedient to you that I go." Fr. Hamon poses the question that we ourselves may be wondering: "How, Lord, can it be useful to Thy apostles to be separated from Thee, who art their light, their strength, their consolation?" Then he answers the question from Jesus' point of view: "They have too natural an attachment to My Humanity, they are too fond of the sensible consolations which My presence makes them enjoy; they must learn to love the God of consolations more than the consolations of God. The heart which desires to belong to God must be detached from all ties to the creature, however excellent the creature, may be. That is why it is useful for them that I go away."

Next, Fr. Hamon addresses the two kinds of aridities of which I previously mentioned:

1. a trial with which God visits fervent souls;

2. an effect or chastisement of tepidity.

So, aridity can be caused for these two reasons, either it is a trial sent by God, or else it is an effect of our own tepidity. The way to tell the difference is by examining our own attitude. When a fervent soul is plunged into aridity by God's doing, the soul languishes in a state of powerless and misery, it feels badly about its coldness of heart and desires to make recompense to God. The tepid soul, on the other hand, may not even notice, and if it does, it doesn't care. While the fervent soul senses the crises and endeavors to overcome it by desiring to do better, the tepid soul feels at ease and has no desire to rise from its state of mediocrity.

The fervent soul, says Fr. Hamon, does not slack in its pious exercises or in its duties in spite of its aridities, which it continues to performs as well as it can. The tepid soul, on the contrary, performs its exercises badly, abridges them or omits them entirely, it will not submit to anything which displeases it.

If we determine that our aridity is from own tepidness, then it is our responsibility to correct it. However, if aridities are a trial from God, then we must accept them without discouragement or distress. Fr. Hamon counsels us to: "Offer to God your heart as dry ground which is exhausted and which thirsts for His grace and His holy love." And while we wait, we must continue to serve Him in peace.

Fr. Hamon further encourages us to remember Christ's afflicted cry upon the cross: "My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken Me?" (Mark 15:34), and to thank Him for having willed to pass through this state of abandonment and aridity in order to encourage us to bear it ourselves.

He also reminds us that God has a right to require from us even things in which we find no pleasure: "Never was a servant authorized not to serve his master for the reason that what he was commanded to do wearied him or gave him no pleasure. Now God is our master, and He has an undeniable right over all our actions, independent of our tastes as well as of our repugnances."

Further, he warns us against a great delusion: when we have no taste for something, we imagine that it is not meritorious or pleasing to God, but this is not true. God does not ask of us to serve Him with a taste for doing so, but to serve Him faithfully in spite of all the weariness we may feel in doing so. "Never does this good Master better appreciate what is done for Him, never do we acquire more merits, than when we triumph over repugnances to follow at every instant the voice of duty."

Fr. Hamon aptly points out: "To perform our duty by overcoming the repugnances of nature… behold, herein lies the supreme merit to which is assured the most beautiful of crowns. Far, then, from works performed with aridity and with weariness being less meritorious, they are richer in merit, and they receive a recompense in proportion to the difficulty they cost us."

When one finds himself in this state, Fr. Hamon recommends the following conduct:

more faithful in performing our exercises of piety

we must keep ourselves united to God.

not to curtail any of our pious exercises, spite of the small amount of taste we have for them

to persevere, although we have no attraction to, in a spirit of recollection and of union with God.

Finally, Fr. Hamon points out how the trial of aridity serves to strengthen us in virtue:

"The only solid virtue is that of the mature man who, being weaned from these sweetnesses, eats the substantial bread of tribulation and trial. It is with the soul as it is with the body. In proportion as we leave childhood behind us, we cease to give the body those tender and delicate attentions which were lavished upon it at our entrance into life; it is subjected to painful exercises, which, whilst fatiguing it, strengthen it. In the same way, God withdraws from the soul the sensible joys, which, by weakening it, would prevent its vigor from being developed. He exercises it by trials of aridity, which fashion it to abnegation, to patience, to love of the cross, and render it more vigorous and capable of great sacrifices. It is thus that strong souls are formed and solid virtues implanted in the heart. Whoever is able amidst weariness and aridities to perform his duty constantly and perfectly, will be capable of the most difficult things, and his robust energy will be superior to all obstacles."

7. How to Profit from Aridity:

To summarize, these are the key strategies for conducting ourselves in times of aridity to best profit from it:

Refuse to grow dull in zeal for prayer. Do not abandon your customary good works. Be willing to continue in your prayers and good works even when you find no pleasure in them. Continue doing your best in your daily duties. Do not give in to feelings of disinterest and disgust.

Finding no help and no sweet consolations, the soul learns to walk by strength of the will alone. Such acts are more meritorious because they are more voluntary. In this way, the soul's love for God becomes more pure because it is disinterested in self.

Temptations reveal our need for God and oblige us to pray, to beg, God to come to our aid, and to place all of our confidence completely in Him.

Aridities are a powerful means of keeping us humble.

"When God hides Himself in the night of aridities and privations, it is only to make the soul desire Him still more. His absence in aridities would then make us desire Him more earnestly, seek for Him with more ardor, find Him with more love, and keep Him in us more watchfully." - Fr. Hamon

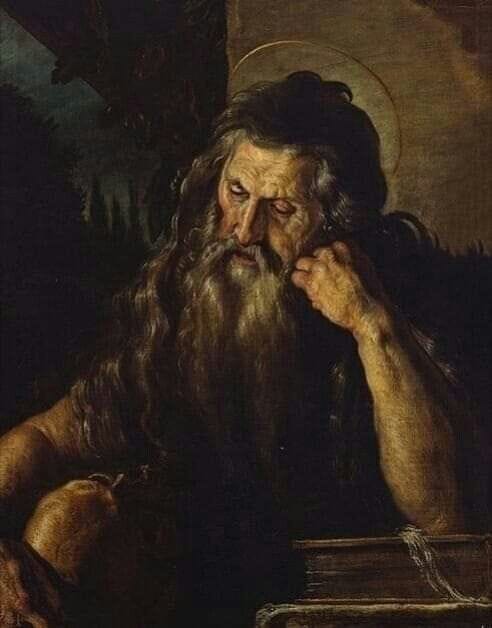

8. Passive Purification and the Three Stages

Now, dear reader, let us move on beyond the basic aridities of the spiritual life and discuss the even more painfully intense passive purifications. There are even greater desolations that a soul experiences as it progresses into the later stages of holiness.

An anonymous Carmelite Tertiary explains that there is a more difficult trial awaiting those who progress further in the spiritual life:

"In the earlier stages of the interior life, we may have alternating times of consolation and dryness, a disinclination for prayer and spiritual duties, but by being faithful to our Rule, and with prayer and good will, we manage to overcome our perverse feelings and have grave to stay in a state of friendship with God. There is, however, a much more difficult and trying time to be gone through by the soul as she climbs higher up the holy hills of our Lord, the Hills of Prayer." 10

Scripture often recalls, even to those who are in a state of grace, the necessity of a more profound conversion toward God.

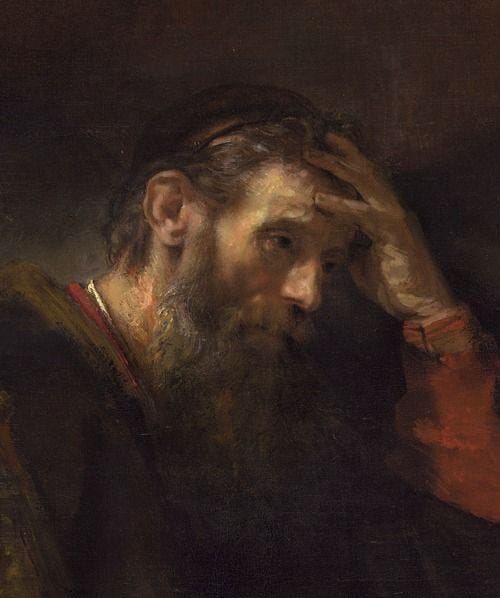

Fr. Lallemant, a French Jesuit priest from the 1600s, explains that two conversions ordinarily occur in the majority of the saints: 1. by which they devote themselves to the service of God, and 2. by which they give themselves entirely to perfection (we see this even in the lives of the Apostles, 1. when Christ called them, and 2. when He sent the Holy Ghost upon them). This "second conversion" is necessary because of the inordinate self-love that still remains in beginners, even after years of their initial conversion. There is often an unconscious egoism which is mingled in the actions of a beginner; therefore, there must be a new and genuine conversion, an even greater turning of the heart to God. 11

All of Christian tradition acknowledges that growth in the spiritual life as marked by three distinct stages: the purgative (the beginner), the illuminative (the proficient), and the unitive (the perfect). St. Bernard describes four degrees of the stages of charity 12 while St. Teresa of Avila imagines the spiritual life progressing through seven mansions. 13 St. Thomas Aquinas sees the traditional three stages as the progression of the soul toward Divine Charity and observes differences among the stages as one grows in love of God. 14

Yet, even as far back as the end of the 2nd century, Clement of Alexandria (150 - 215) describes the "spiritual ascent," every phase of which brings a soul closer to the state of the perfect man (that St. Paul speaks of in Ephesians). According to Clement, the perfect are "tranquilized souls," in which charity (love of God) dominates. 15

St. Ephraim (306 -373) said that the privilege of the perfect life is obtained by docility to the Holy Ghost, which can only happen after we have conquered our passions, destroyed every inordinate natural affection in ourselves, and emptied our minds of every preoccupation useless to salvation. Only then can the Holy Ghost, finding our souls at rest, communicate a new power to our intellect, putting light in our hearts. He compares our hearts to a lamp that already has the wick and oil ready, so that the Holy Ghost only needs to light it. "Therefore, above all things," he says, "let us prepare our souls for the reception of the divine light and so render ourselves worthy of the gifts of God." 16

Gregory of Nyssa (335 – 394) taught that, in order to be admitted into the contemplation of the Divine Nature and union with God, we must first detach ourselves from creatures and live by Christ. 17

Cassian (360 - 435) shows that the soul prepares for divine contemplation by a life of prayer to obtain pardon for sins, and the practice of virtue (especially a desire for greater charity), until this prayer ends by becoming a prayer of all fire, formed by the contemplation of God alone and by the ardor of burning charity. 18

St. Augustine (354 - 430) distinguishes several degrees, insisting that, in the struggle against sin, there is a difficult work of purification followed by the entrance into light, and finally into divine union. 19

In the 6th century, St. Gregory the Great (540 - 604) speaks of the division of 3 degrees in the spiritual life: the struggle against sin, the active life of virtue, and finally the contemplative life, which is of the perfect. 20

I stress all of this only to emphasize that growth in the spiritual life ordinarily happens in three successive stages, with each of the stages have its own distinction. The first stage is the purgation of sin, the second stage is the growth of virtue, and the third stage is union with God by charity. And no matter how far advanced one is in the spiritual life, there is always a continual need of greater purification for more growth.

“The branch that does yield fruit, He trims clean, so that it may yield more fruit.” - John 15:2

St. Catherine of Siena discusses the second conversion in Chapters 60 and 63 of her Dialogue. In reference to imperfect love of God, she cites as an example the second conversion of Peter during the Passion. She says that the imperfect soul loves the Lord with a love that is mercenary (concerned with making a profit or finding benefit for oneself). Often, at this time, God permits us to fall into a fault in order to humiliate us and oblige us to enter into ourselves, just as Peter did when, immediately after his failure, Christ looked at him and he "wept bitterly."

St. Catherine tell us that it is necessary to leave this imperfect state in which a person is serving God more or less through self-interest; but in order to leave this imperfect state, the soul must be converted so that it can cease to seek self and truly go in search of God by way of abnegation.

Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange explains in his work The Three Ages of the Spiritual Life: "To reach the spiritual age of the perfect, one must grow in charity. To attain it, we need abnegation, a great docility to the Holy Ghost through the exercise of the seven gifts, and the generous acceptance of the crosses and purifications which will destroy egoism and self-life and definitely assure the uncontested primacy of the love of God."

Saint Thomas Aquinas wrote that no one is so pure in this life that he no longer needs to be more and more purified. 21 It's a process that all Christians must undergo. No matter how holy they are, there is always a greater degree of holiness that can be attained. In order that the just who bear fruit may bear still more, God frequently cuts away in them whatever is superfluous. He purifies them by sending them tribulations and permitting temptations in the midst of which they show themselves more generous and stronger.

These are the very same passive purifications of which St. John of the Cross spoke of at length in his work, The Dark Night of the Soul. Before St. John of the Cross, we find St. Gregory the Great noting these painful passive purifications that "dry up all sensual affection in us," which he says are for the purpose of preparing us for contemplation and union with God.22 Yet, no one has described these trials better than St. John of the Cross. He explains that aridity is a means by which God purifies the soul, removing attachments to worldly things and preparing the soul for deeper union with Him. He calls the second conversion the passive purification of the senses and says that it marks the entrance into the illuminative way.

St. John of the Cross describes a road which leads most surely and rapidly to the full perfection of Christian life, declaring that a soul cannot reach it without undergoing the passive purification of the senses (the entrance into the illuminative way) and the passive purification of the spirit (the entrance into the unitive way).

"Souls begin to enter the dark night when God is drawing them out of the state of beginners and is leading them into that of proficients, that having passed through it, they may arrive at the state of the perfect, which is divine union with God."

He also tells us that we cannot do this by our own efforts.

"For, after all the efforts of the soul, it cannot by any exertion of its own actively purify itself so as to be in the slightest degree fit for divine union of perfection in the love of God, unless God Himself takes it into His own hands and purifies it in the fire."

In The Spiritual Life, Rev. Tanquerey explains that even advanced souls are subject to many imperfections, and in order to purify them still more and to prepare them for a higher degree of contemplation, God sends them these passive trials (called "passive" because it is God Himself who causes them and the soul has but to accept them patiently).

Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange says, "Passive purification is indeed the normal way of sanctity. It is the purification that must be undergone on earth while meriting (or else in purgatory without meriting) in order to reach perfect purity of soul, without which one cannot enter heaven. It is truly the normal way of sanctity of the Christian life." 23

Finally, Fr. Marie-Dominique Molinie explains it thus: "After many years of Christian life we reach a kind of ceiling in which we cannot get past by ourselves. We make progress, but within very confined limits. By ourselves we can do nothing more. But what is impossible to men is possible to God, and we do not have the right to doubt it. So, if we truly believe this, there is still one thing we can do. We can say to God, 'I accept the treatment,' and we can sign ourselves into the hospital - the monastery of passive purification. From there, God knows what to do. He gives us the Blood of Christ which has the power to work the miracle of our complete sanctification and turn us into beings who offer no resistance to the will of God. These are the saints." 24

9. Coping with This Aridity

In this state of aridity and powerlessness, one must not become discouraged or abandon prayer as if it were useless. On the contrary, it becomes even more fruitful for the soul to persevere.

When experiencing a passive purification, the most important thing to remember is that this is a necessary and normal part of spiritual growth. According to the unanimous testimony of the Fathers and Saints, a soul cannot advance in the spiritual life by its own means, but only by being docile to God and His interior work in the soul. As St. Ephraim said, we "prepare the wick and the oil," that is, we eliminate sin and practice virtue, but only God can light the lamp, and only when it is ready. The upward ascent toward God is one that we will be climbing for our entire earthly lives. God alone can lead the soul into its deepest union with Himself, and He does this by way of purification. In essence, we cannot be purified of our imperfections until God leads us into the passive purgation of the dark night. When we experience these trials, it is good to remember that it is willed by God in order to purify us, because without this purification we cannot reach union with Him, so ultimately it is for our greatest good.

Therefore, rejoice! You are entering "the narrow way," into a new and higher life.

10. The Abomination of Desolation

This dark night is an extremely painful process that comes with many temptations. In particular, a soul will experience temptations against the three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity; but also, temptations against chastity, patience, and peace of soul. A soul in this state, feeling nothing, can imagine that it believes nothing; being deprived of consolation, it can believe itself abandoned; amidst all this weariness, it is tempted to complain; and it can become obsessed with scruples.

Although St. John of the Cross admits that these intense feelings are impossible to communicate to someone unless they themselves have felt it, one of the best explanations I have read comes from that anonymous Carmelite Tertiary that I quoted earlier. When he speaks of passive purification, he compares it with a swimmer making for the shore:

"At first he swims vigorously, and he believes it is his own effort which is carrying him forward. So it is, in part, but the tide as it rushes in bears him forward also at a great pace. If he then relaxes his effort at swimming but keeps his body heading for the shore, he will see that the tide itself by the force of the waves will bear him safely home. So it is with the soul in this new stage of her interior life. She must relax her activity and let God do His part. Her efforts are still needed, but only in the sense of resigning herself entirely to the will of God without murmuring or resisting. The tides of the mighty ocean of His charity will bear her safely home if she makes first the necessary effort of conformity to His will.

"Our Divine Spouse brings upon her now suffering of every sort to crush her but not to overwhelm her. It may be that she has to suffer spiritually, or physically, or both. In some cases, Almighty God brings anguish of every kind upon her. There may be illness, loss of reputation, loss of means and friends ... Added to all of this, God Himself seems to withdraw from her. She now begins to understand faintly the sufferings of her Lord in the Garden and in His awful dereliction. Prayer seems impossible, and there is no relief to be obtained from the Sacraments, which one does not even seem to believe.”

“The Abomination of desolation has descended on the poor soul, and there is no one and nothing to comfort her. God himself only knows how long such a time will last. All that the soul can do is utter cries of misery, and she feels like she is speaking to empty air. For years, it may be, she has done her best to be recollected in God, to refer all her thoughts, words and actions to Him, to purge herself by prayer and penance from her sins, and to unite to Him by the Sacraments. She has gradually learned to know and to realize Him as the center of her soul, and now, in a flash, God seems to have altogether disappeared from His creation and from her own soul.”

“God seems to us to be but a remembrance, and the hardest part of the suffering is that hope seems almost extinguished. The peculiar bitterness is that we have left all - sin, the world, and ourselves for God - and now He seems to have left us! No one can describe the suffering. There is nothing but suffering and absolutely no consolation at all to be perceived by us in any shape or form. There is nothing whatever to do but to be patient and let God do what He wishes with us." 25

And how to endure such a state of desolation?

“Such a time comes in one form or another to everyone who deliberately sets himself to a prayerful life. There is nothing to do but set one's teeth and endure it. Prayer is often an absolutely impossibility, in the sense which one has hitherto understood it. All we can do, and all we must do, is resign ourselves to suffer for as long as it pleases God to let us suffer.”

"Other souls have had the same trial and have been brought safely through it. We must go on attempting to behave as normally as possible and God will remember and have mercy on us. We shall learn to know ourselves and our nothingness and vileness, and in no other way could the lesson be learned. God must reign in us, and it is only by suffering that His Kingdom can be perfectly and solidly established in us." 26

11. The Saints Suffered from Aridity

Many saints experienced periods of spiritual aridity and struggled with it throughout their lives.

St. Bernard, gives expression to his feelings in the following passage: ‘‘How is my heart become as earth without water? So hard has it grown that I can no longer extract from it any tears of compunction. Psalmody, pious reading, and prayer have lost their attractions for me. My customary communings with God have ceased to be a source of light and consolation. Where now is that intoxication of soul? that tranquillity of heart? that peace and joy in the Holy Spirit?” 27

‘‘I feel such dryness,” says St. Alphonsus, ‘‘such spiritual desolation, that I can no longer find God either in prayer or in Holy Communion. Both the Passion of Our Lord and the Blessed Sacrament have lost their power to touch me. I have become insensible to all feelings of devotion. It seems to me that I am a soul without either faith, hope, or charity—in a word, a soul forsaken by God." 28

In his Confessions, St. Augustine reflects on his own experiences of spiritual dryness and how he overcame it through perseverance and trust in God. One of his most notable quotes on this topic is: "Let us endure, let us endure ... No suffering will be so richly rewarded as weariness of heart and spiritual pain. These are the greatest sufferings there are, and so they are deserving of greater fruit."

St. Therese of Lisieux wrote in her autobiography: "Do not think that I am overwhelmed with consolations. Far from it! My joy consists in being deprived of all joy here on earth. Jesus does not guide me openly: I neither see nor hear Him."

She wrote elsewhere in a letter: “I thank my Jesus for making me walk the ways of darkness. I am enjoying a profound peace in them. I would willingly consent to pass my whole religious life in this subterranean obscurity into which He has brought me. My sole desire is that my darkness may obtain light for sinners. I feel happy, yes, very happy at being left without consolation.’ 29

St. Francis de Sales wrote the following in a letter to St. Jane de Chantal: “‘Woman, why weepest thou?’ (John, 20:15). But you must not remain a woman, you must have the heart of a man. And provided you have a firm purpose to live and die in the service of God, you must not worry about the darkness, or the impotence, or the other obstacles to your advancement. We cannot avoid such obstacles here on earth, but in paradise we shall have none to encounter. ... It is God’s will that our misery should be the throne of His mercy, our impotence the seat of His omnipotence.’’ 30 He went on to exhort her to remain humble, tranquil, meek, and confident in the midst of her helplessness and obscurity. He would have her to avoid all impatience and agitation, to resign herself to the darkness of her soul, and to embrace the cross courageously, generously, and resolutely.

St. Alphonsus remarks: “All the saints had to suffer these aridities, these spiritual desolations. In fact, aridities were more usual with them than sensible devotion. God bestows transient favors of this kind only seldom, and usually on souls as yet very feeble, in order that they may not come to. a stand-still on the road to perfection. As for the delights that are to be the reward of our fidelity, it is only in paradise we can expect to enjoy them. ... Whenever you feel forsaken, comfort yourself with the thought that you have the Divine Consoler with you. You complain of an aridity of two years’ duration. But St. Jane de Chantal had to endure that trial during forty years. St. Marie-Madeleine de Pazzi for five years had to support continual pains and temptations without being granted the slightest relief." 31

St. Francis of Assisi spent two years in such desolation that he seemed to have been abandoned by God. But after he had humbly submitted to this terrible trial, the Saviour restored to him in an instant his usual happy tranquility. This made St. Francis de Sales concludes that, ‘‘since the greatest servants of God were subjected to these afflictions, those who are the last and least in His service should not be surprised if they feel something of them also." 32

12. Advice from the Saints

Although this whole article is teeming with advice from saints about how to cope with spiritual aridity and passive purification, here is some final advice from two very different, yet very holy bishops:

St. Francis de Sales:

‘‘It will happen that you will enjoy no consolation in your practices of devotion. That, undoubtedly, is the good-pleasure of God. Hence the necessity to remain absolutely indifferent to consolation or desolation. This self-forgetfulness implies abandonment to the divine goodpleasure in all temptations, aridities, drynesses, aversions, and repugnances. For we can see that good-pleasure in all these states of soul, when they are not due to any fault on our part, and when they contain nothing sinful.”

‘‘If consolations are offered you, receive them with gratitude; if they are refused, desire them not, but try to keep your heart ready to welcome whatsoever Providence may send, and as far as possible with the same satisfaction.... You must have a strong resolution never to give up prayer, no matter what difficulties you may encounter in that holy exercise. And you must never apply yourself to it, preoccupied with a longing to be consoled and favoured. For that would not be conforming your will to Our Lord’s, Who desires that we should enter prayer resolved to suffer the affliction of continual distractions, aridities, and disgust, should this be His good-pleasure, and to be as content in this state as if we enjoyed a superabundance of consolations and perfect tranquility. Provided we always accommodate our wills to the will of His Divine Majesty, remaining in an attitude of simple expectation and in a disposition to receive lovingly whatever Providence may ordain, whether in our prayer or outside it, He will see to it that everything is made conducive to our profit and pleasing in His sight.” 33

St. Jane de Chantal, speaking of St. Francis de Sales:

”He used to say that the proper way to serve God was to follow Him without any support from consolation or sentiment, without any light but that of pure and simple faith. That is why he loved dereliction, abandonment, and interior desolation. He once told me that he didn’t mind whether he was in a state of consolation or desolation. When Our Lord granted him sensible devotion he received it with simplicity; if it were denied him, he thought no more of it.” 34

St. Alphonsus Ligouri:

“I do not pretend that we should suffer no affliction at seeing ourselves deprived of God’s sensible presence. We cannot help being afflicted at such a loss, or even complaining of it, since our Divine Saviour Himself complained of it on the cross. But we should imitate His perfect resignation and that of the saints. They had more experience of aridities than of sensible consolations; and what they longed and prayed for all their lives was rather spiritual fervor in suffering than sensible fervor in enjoyment. Are you in a state of aridity? Be patient, and do not neglect any of your ordinary devotions, particularly mental prayer. Do not imitate those persons who, when consolation leaves them, show how little supernatural they are by abandoning their pious enterprise, relaxing their austerities, and ceasing to guard their senses; so that they lose all the fruits of their former labors. Perhaps it appears to you that your aridities are the punishment of your faults? Then accept the merciful chastisement with humility, and do all in your power to remove the cause of your lamentable condition; that is, such or such a natural affection, a want of habitual recollection, an eagerness to see, to know, and to say everything. Remember that, if you received your desert, you would never more have experience of joy. Above all, practise resignation, and trust more than ever in the goodness of God. For now you are given a special opportunity of rendering yourself particularly dear to your Divine Spouse. Continue to seek Him, therefore, with good courage. Possibly He will not return with His consolations. What matter, so long as He gives you the grace to love Him and to accomplish all that He wills? A strong love is more pleasing to God than a tender love. Let us humbly resign ourselves to the divine will, and we shall discover that desolation is more to our advantage than any sensible devotion.” 35

I conclude with this beautiful thought from Fr. Lehodey:

"Happy the souls who, following the example of St. Thérése of the Child Jesus, make it their aim to console their sweet Master instead of always demanding to be consoled by Him." 36

Rev. Adolph Tanquerey, The Spiritual Life, Ch. 5, paragraph 925.

Dark Night of the Soul I, 9,2

Ibid

Ibid

Fr. Lehodey, Holy Abandonment, Ch. XI

The Spiritual Life

Prayer: The Great Means of Salvation and Perfection

Summa Theologica, Part II-II, Question 166, Article 3.

Fr. Andrea Jean Marie Hamon discusses aridity in Volume 2 of Meditations for All the Days of the Year.

Thesaurus Fidelium

Doctrine Spirituelle by Fr. Jean Joseph Lallemant

On the Love of God by St. Bernard

Interior Castle by St. Teresa of Avila

Summa Theologica, Part 2B, The Virtue of Charity

Stromata

Hymns on Paradise

Commentary on the Song of Songs

The Conferences

De Quantitate Animae, Chapter 33, Nos. 70-76

Moral Reflections on Job

Summa Theologica, Part II-II, Question 188, Article 6

On Commandments and Doctrines

The Three Ages of the Interior Life

The Courage to Be Afraid)

Thesaurus Fidelium

Ibid

Serm. in Cant., liv.

Peines intér., 2.

Lettre, 4a la R. M. Agnès et Souv

Letires, 417 et 530.

Conf., 5, 5, et Peines inter., 2..

Vis dévote, P. IV, c. xv

Entret., ii, vi, xviii, xxi.

Vie, 1, v, et append., Lettre de Ste. J.-F. de Chantal

Relig. Sanct., ¢. xiii; Am. env., c. xiii; Conf., 5, 5.

Holy Abandonment, Chapter XII

Beautiful and so informative. I took in every word. Thank you!