Birth and Early Life

Margaret Metola was born in Italy in 1287, just before the Renaissance began. She was born in Metola Castle, located in the central Apennines, in a region known as Massa Trabaria. It was a heavily wooded Papal State.

Margaret was born into a period of intense turmoil in Italy, with the country suffering from violent and endless wars.

Margaret's parents, Parisio and Emilia, were of considerable social and political standing. Parisio held the position of "Captain of the People" at the Castle of Metola, a role that had been occupied by a number of his ancestors. In times of war, he served as commander in chief of the armies. He was a fearless and competent soldier, but also a proud, worldly, and hot-tempered man. Both Parisio and Emilia hailed from prominent families, yet neither could be considered pious in their religious practices.

Upon learning that Emilia was with child, they anticipated the birth of a son, an heir to continue the family legacy. Instead, Margaret entered the world, and they were dreadfully disappointed. Not only did she have the audacity to be a girl, but worse still, she had numerous physical challenges.

Margaret was not a pretty baby, but her appearance was the least of her problems. She was unusually small, diagnosed with a condition we now know as dwarfism; she had a curvature in her spine and a hunchback; her right leg was shorter than her left, and to add to her difficulties, she was also blind.

Her parents were not the type to be touched with compassion, so instead of rendering pity to their baby, they viewed her with disgust. In their intense shame (and to keep their perceived “misfortune” a secret), they decided to spread the false news that their child was sickly and likely to die. Then, they kept Margaret’s existence hidden from all.

Padre Cappallano served as priest of the parish of Metola and was also the chaplain of the fort. He rightly demanded that the baby be baptized, however during his time there existed a custom in which baptisms were performed in the cathedral. This meant the baby had to be taken to Mercatello to be baptized and risk possible public exposure.

Parisio and Emilia delegated the task to a maid, indicating that they didn’t care what baptismal name was chosen. So, it was the maid who chose the name Margaret, a name which means pearl, a lovely little symbol of perfection and beauty. It is unknown if the maid knew the significance of the name she chose or not, but it was certainly an apparent contradiction given Margaret’s outward appearance. Yet, it would be the perfect token of the inner radiance that would adorn her soul.

In their shame and embarrassment, Parisio and Emilia kept the child hidden away for years. She was cared for by a nurse, and the chaplain gave her religious instruction. From a young age, the chaplain reported that Margaret was very devout in her religion, and that he was surprised by her remarkable intelligence, and that despite her difficult family circumstances, she remained exceptionally cheerful and friendly. Apparently stubbornly immovable in their disapproval of the child, her parents were untouched by these reports of piety and intelligence in their daughter. She was not what they had hoped for, and they remained bitterly disappointed.

At the age of 6, she was almost publicly discovered in the castle halls by curious visitors. Her parents were so mortified by this almost-discovery that they took definite action to ensure it would never happen again. From then on, Margaret was exiled to a small room attached to the chapel, completely walled in so that she could not leave. Her parents effectively made her a prisoner, to conceal what they believed was their greatest shame. One act of mercy, whether intentional or not, was that Margaret still had access to Holy Mass and the Sacraments.

The chaplain continued to patiently instruct Margaret in the truths of the faith. He described her mind as “luminous.” Apparently, Margaret possessed a brilliant mind. One biographer remarked on a resemblance between Margaret's early intelligence and that of St. Catherine of Siena and St. Rose of Lima, when they were of the same age.

It was through the patient, loving religious instruction of the priest that Margaret was able to accept her suffering cheerfully. She desired to grow in virtue and draw closer to the God, Who she knew had made her and loved her. But she also knew the road she had to take was the same as her Savior: the road of suffering. She understood that God allowed her physical suffering for the greater good of her soul, which prompted her to accept it as a gift from God. Margaret, although only a child, had discovered and willfully embraced the great secret of sanctification: suffering. She knew that it was her path to union with God. As if she didn’t have enough natural suffering to deal with, Margaret desired to practice even more voluntary penance, so she bound herself to a strict fast and wore a hairshirt.

Perhaps even more remarkable was that, despite the harsh treatment of her parents, Margaret never grew bitter or angry toward them. In what can only be described as heroic virtue, she maintained feelings of love and devotion, and was even grateful for their care, meager as it was.

Abandonment

After Margaret had spent a decade in her confined quarters, Emilia was forced to flee the castle due to an impending invasion. It's a wonder that she took Margaret with her at all (one has to wonder what compelled her to care for the child’s safety). Concealing Margaret beneath a dark veil to ensure no one would recognize her, she journeyed to another castle in Mercatello. Unfortunately for Margaret, this release from one prison was merely a transfer to another: a small, vault-like cell containing nothing but a pallet and wooden bench. However, the worst agony for Margaret was not her new cell, but the deprivation of Mass, the Sacraments, and the friendship of the chaplain who had taught her so much. An accumulation of trials was befalling her, but an even greater tragedy was lurking.

When Parisio returned from war, Emilia convinced him to take Margaret to the city of Castello to pray for a cure. Apparently, a lay Franciscan tertiary named Fra Giacomo had recently died, and people were claiming miracles at his tomb. Surprisingly, Parisio not only agreed to make the journey over the Apennine Mountains to the Franciscan church, but he expressed a keen interest and enthusiasm about the pilgrimage. Emilia knew her husband was a ruthless man, but did she realize the full reason for his enthusiasm? He was determined to rid himself of his “problem” permanently.

Margaret was around 16 years old when her parents brought her to the church, hoping for miraculous healing. They brought her as close to Fra Giacomo’s tomb as they could, then commanded her to pray with all her might for a cure. As Margaret became absorbed in prayer, her parents left the church to walk around town. Sometime later, they returned to the church and found Margaret still enrapt in prayer. No miracle had taken place. Parisio and Emilia’s patience was entirely spent. Callously, quickly, and quietly, they fled town without Margaret.

Fr. William R. Bonniwell, O.P., writes:

“The blind cultivate their sense of hearing to such a degree that when people approach them, they can usually recognize their different friends merely by listening to their footsteps. During the remaining years of Margaret’s life, she would hear the footsteps of a thousand people. But no matter how long or attentively she would listen, never again would she hear the footsteps of the two persons she knew so well. For the noble lord and lady of Metola had abandoned their daughter.”

Maragret remained obedient to her parents’ initial command, staying in the church and awaiting their return. What else could she do? She was blind, lame, and alone in an unfamiliar city. Eventually, the sexton came to lock the doors of the church for the night and found Margaret. She had to leave the church, he told her, so she went outside to wait for her parents.

I don’t know how long she waited or when she realized that she had been abandoned, but in time, she became a poor beggar in the streets. At first, the people viewed her suspiciously, thinking she was pretending to be blind and crippled as a scam to get money, but eventually her cheerful disposition won them over and they saw her sincerity. She was so patient in her suffering, and so happy despite her circumstances, that their suspicions turned to admiration.

For some time, Margaret went from home to home among the poor of the town, each poor family doing what they could to help and support her. When the strain became too much, Margaret would be moved to another household. Thus, she passed from house to house, family to family.

Difficulties

Margaret’s holiness was noticed by all; thus, Margaret was eventually invited to join a convent of nuns. After a life of solitude, we can imagine it must have been a great joy for Margaret to live in a community of sisters. But it wasn’t long before Margaret was the center of a developing conflict.

The sisters had grown lax in their observance of the Rule, but Margaret was not the type to neglect her duties. Margaret decided, through prayer and advice from her confessor, that she would live according to the Rule, even if the other nuns weren’t. Her obedience to the Rule became a problem, as her quiet example made them all look bad in comparison. The novice prioress encouraged Margaret to dismiss the Rule on silence in order to be sociable and to practice charity above all other virtues. Even the Mother Prioress told Margaret to forgo the old Rule and to practice the latest custom instead. Maragret, through speaking with her confessor, was sure that by following the Rule she was doing what was most pleasing to God, so she remained firm in her decision to continue following the Rule, rather than conform to the lax custom.

Since she would not compromise, she was expelled. This was yet another cross for Margaret to carry. But as usual, she accepted her suffering cheerfully and harbored no bitterness toward the nuns.

Margaret’s expulsion from the convent brought with it even more hardship, as the townspeople resorted to public derision and contempt. What had Margeret done to get kicked out of the convent? She was laughed at and considered stupid and of no value. Margaret did not defend herself, nor speak ill of the nuns at the convent. But after months of ridicule and sneering remarks, the people came to realize, by Margaret’s charitable silence, that they had been wrong.

Margaret felt nothing but gratitude towards the townspeople and the nuns for their care of her. She was so appreciative, that she desired to give them something in return. She opened a house for poor persons, cared for the sick and the suffering, and taught the children their catechism. Her orphanage/school became a daycare: people would leave their children in her care while they worked.

Religious Vocation

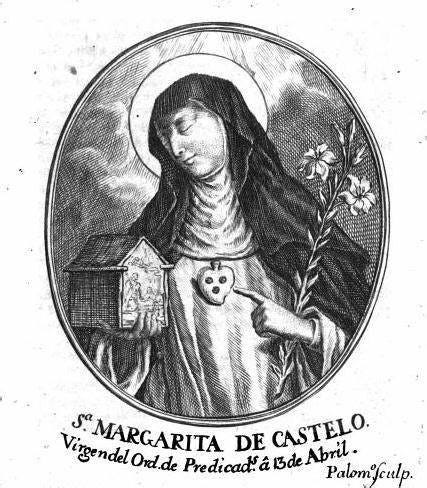

Margaret also began to attend Mass every morning at the Dominican church, and she became acquainted with some of the members of the “Mantellate,” an Italian term for a group of lay women who were members of the Order of Penance of St. Dominic. (Eventually, these women would develop into the present day Third Order of St. Dominic).

These women desired to live a religious life, but for whatever reason, they were not able to enter a convent. Instead, they affiliated themselves with the Dominican Order by joining the Third Order of Penance. They lived in their own homes, but were bound by a Rule of Life, and they wore the Dominican religious habit. The name for these Sisters, “the Mantellate,” came from the black mantella (cloak) that was part of their habit.

After getting to know Margaret, the Mantellate wanted her to join their Order. At first, the Dominican priest would not permit Margaret to join because she was not of eligible age. At this time in history, the Order generally only accepted “mature” widows, although an older married woman could join with the permission of her husband. Young women were not permitted. Be that as it may, an exception was eventually made for Margaret after a careful investigation into her faith, character, and reputation. She was the first young, unmarried woman admitted to the Order.

Margaret’s Dominican habit was not only a reminder that her life was dedicated to the service of God, but it was also a sign that she was part of a family again - the great religious family of Dominicans. She considered the Dominican friars and nuns as her true brothers and sisters.

The Rule of the Dominicans emphasized especially study, prayer, and penance. Study mostly applied to the First Order - the friars - but prayer and penance were obligatory for all Dominics, whether First, Second, or Third Order. St. Dominic had been strongly influenced by the writings of St. Paul regarding the necessity of mortification, if one wanted to conquer inordinate passions and gain an incorruptible crown. This is why he fixed penance for his Order. Her life became a true life of constant prayer, penance, and charity.

Although she did not live in a convent, she chose to follow the routine of one as closely as possible. She prayed the 150 Psalms every day, as well as the Office of the Blessed Virgin and the Office of the Holy Cross. Her biographer states that she had somehow learned them in a miraculous way and would recite them from memory.

When Margaret would hear the bell announcing Matins, she knew that the friars were praying, and she would rise to join in their prayers in spirit. She would not go back to sleep but spent the rest of the night in meditation.

She obtained permission from her confessor to imitate St. Dominic in the practice of scourging. In the true Dominican spirit to save souls, she felt that if her suffering could save even just one soul, she would gladly endure the agony.

Her heart overflowed with love for others. In fact, Margaret was known to often say, “If you only knew what I have in my heart!” Despite her own infirmities, Margaret helped the sick and the dying. The townspeople would frequently see her limping to the side of anyone in agony, and she would do everything she could to help them. When she learned that the prisoners in jail were half-starved and living in inhumane conditions, she began to visit them and tried to improve their living conditions. Most women were not allowed to administer to the prisoners because it was such a foul place, filled with disease and sickness, but Margaret greatly desired to care for these miserable prisoners, perhaps because of her own time being imprisoned.

Death

On April 13th, 1320, at the age of 33, Margaret died.

Poor religious would typically be buried, but the people of Castello caused an uproar, insisting that she be buried in the church, an honor reserved for saints. At first the priest resisted, but when a disabled girl was cured at Margaret’s funeral, he allowed for her burial in the church.

The Incorruptibles published by TAN books, relates the following:

“On June 9, 1558, the bishop authorized the transfer of the Beata’s remains to a new coffin after it was noticed that the original one was rotting away. The exhumation was undertaken in the presence of a number of official witnesses who were awe-stricken when the coffin was opened. While the clothing on the body had crumbled to dust, the body itself was found to be perfectly preserved, as though Margaret had just died.”

Margaret’s body was reclothed in a fresh habit and placed in a new coffin. It was during this transfer that her body was discovered incorrupt, and another remarkable thing was discovered: Inside her heart were found three pearls on which appeared to be carved religious symbols: the images of Our Lord, the Blessed Virgin, and St. Joseph. One cannot help but remember her exclamation, “If only you knew what I have in my heart!” For this reason, you will see Margaret depicted in art holding a heart with three pearls on it. (According to her biographer, Margaret possessed a devotion to St. Joseph at a time when it was not common in the Western Church).

In 1609, the Church officially recognized Margaret’s sanctity, pronouncing her a Blessed and designating April 13th as her feast day. And after 700 years of being honored as a miracle worker, she was canonized by way of an equivalent canonization, by Pope Francis in 2021.

Patronage

St. Margaret has become an important patroness of the pro-life movement, she is considered the “‘patroness for the unwanted.” The Sisters of Life venerate her as “a beautiful icon of the dignity of every human life, no matter what its challenges.” Not only was St. Margaret herself rejected and abandoned by her own parents, but she never let this embitter her. Instead, she allowed it to transform her into an icon of compassion as she turned around and ministered to the needs of the sick, poor, rejected, and abandoned.

Margaret’s incredible example of forgiveness continues to inspire awe among those who become acquainted with her biography. She never became resentful of her parents. She never used her challenges or sufferings as an excuse to not practice a life of holiness. She had every reason to be angry at her circumstances, but she never fell into self-pity or held a grudge against anyone.

Margaret lived up to her name, pearl. By the grace of Christ within her and her cooperation with that grace, her soul was truly a hidden pearl. She made good use of all the graces given to her, using them as strength to imitate Christ in His virtues and heroic love.

St. Margaret of Castello, pray for us.

Thankyou for sharing and creating writings such as these. They go deep with me. I treasure them.