Christian Tradition of Head Coverings for Women

There is a long-standing traditional practice for Christian women to cover their heads. This practice comes from Scripture and was carried on by the Church since the time of the Apostles.

1. Ancient Cultures Practiced Head-Covering

It was customary for most women in the ancient Near East, Mesopotamia, and the Greco-Roman world to cover their hair when they went outside the home, although “rules” and customs varied according to culture and religion. Varying laws and customs existed across times and cultures.

In biblical times, the Old Testament references women wearing coverings, however it does not explicitly state that they are mandatory. In Genesis 24, Rebekah sees Isaac in the distance and asks the servant, “Who is that man?” When the servant replies, “It is my master,” Rebekah covers herself with a veil. From other passages we can tell that the unveiling of a woman’s hair was considered a humiliation and a punishment (see: Isa. 3:17; Num. 5:18; III Macc. 4:6; Daniel 13:32).

In the story of Susanna (from Daniel 13), Susanna wears a veil that covers not only her head but her face as well, and it is “wicked men” who command that her face be uncovered. We can see that, biblically speaking, women's head coverings were an accepted practice for the Jewish people, as it was regarded as a thing of virtue and dignity and removal of the veil in public was a symbol of shame and disgrace.

2. For Christians, the basis of a woman covering her head comes from Scripture.

St. Paul teaches in 1 Corinthians 11:

[2] Now I praise you, brethren, that in all things you are mindful of me: and keep my ordinances as I have delivered them to you. [3] But I would have you know, that the head of every man is Christ; and the head of the woman is the man; and the head of Christ is God. [4] Every man praying or prophesying with his head covered, disgraceth his head. [5] But every woman praying or prophesying with her head not covered, disgraceth her head: for it is all one as if she were shaven. [6] For if a woman be not covered, let her be shorn. But if it be a shame to a woman to be shorn or made bald, let her cover her head. [7] The man indeed ought not to cover his head, because he is the image and glory of God; but the woman is the glory of the man. [8] For the man is not of the woman, but the woman of the man. [9] For the man was not created for the woman, but the woman for the man. [10] Therefore ought the woman to have a power over her head, because of the angels.

In the beginning of his letter, St. Paul is commanding the Corinthians to keep the ordinances (also translated traditions) that he has passed on to them. He immediately then says that every man should uncover his head during prayer and every woman should cover her head during prayer. This is what St. Paul passes on to us: “every woman praying or prophesying with her head not covered, disgraceth her head.” He says that a woman who prays with her head uncovered brings disgrace upon herself. St. Paul was not content to state this once but reiterates himself just a few verses on, stating again that a woman ought to have “a power” (also translated “an authority”) over her head, “because of the angels.”

What reason does St. Paul give for such an expectation? “The head of every man is Christ; and the head of the woman is the man,” “The man indeed ought not to cover his head, because he is the image and glory of God; but the woman is the glory of the man. For the man is not of the woman, but the woman of the man.” His reasoning is the natural order of creation, as ordained by God. It’s because woman is the glory of man, is of the man, was created for the man. This goes back to Genesis, when God made them male and female, and woman was “taken out of man.” (Gen 2:23). At no time does St. Paul indicates that he wants them to acquiesce to local custom or that his teachings are for the purpose of conforming with the surrounding culture. The veiling of the woman, for St. Paul, is an outward sign of the acceptance of God’s order, and His divine purpose in creation.

St. Paul states later on in this same letter that "the things I am writing to you are the Lord's commandments" (1 Cor. 14:37), as though his teachings are not his private opinion but the desire of Our Lord. Remember that St. Peter taught us in II Peter 1:20: “That no prophecy of scripture is made by private interpretation. For prophecy came not by the will of man at any time: but the holy men of God spoke, inspired by the Holy Ghost.”

3. The Early Church

The Early Church continued the biblical ordinance passed on from St. Paul. This is clearly and easily attested by the writings of the early Christians and Church Fathers. They did not cease to preach this teaching received from the holy Apostle.

It is worth taking a look at what they had to say, and here’s why: in addition to the teaching of the Magisterium, tradition is also to be found in the teaching of the Fathers. The reason for attributing to them this particular importance is that they are the first successors of the Apostles, they are the first to have received the heritage, the deposit. They are the closest source.

This does not mean that each Father’s writings are infallible – in fact, in some instances the Fathers contradict each other. It is the unanimity of the Fathers that is the criterion of infallibility. That is why the Counsils use the unanimity of the Fathers as a mark of truth.

Pope Linus (died approx 76-79 A.D.) was the successor to Peter as bishop of Rome. From “The Liber Pontificalis” (~530AD), a book that chronicles the history of Roman bishops, we learn about the earliest reference to head covering outside of Scripture. It says this about Pope Linus in his biography: “He, by direction of the blessed Peter, decreed that a woman must veil her head to come into the church.” (1)

Irenaeus (c. 130 – c. 202), the last living connection to the Apostles, explained: "A woman ought to have a veil [κάλυμμα, kalumma] upon her head, because of the angels." He explains that the "power" on a woman's head when praying and prophesying was a cloth veil.” (2)

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215 AD) wrote: "Let the woman observe this, further. Let her be entirely covered, unless she happens to be at home. For that style of dress is grave, and protects from being gazed at. And she will never fall, who puts before her eyes modesty, and her shawl; nor will she invite another to fall into sin by uncovering her face. For this is the wish of the Word, since it is becoming for her to pray veiled." (3)

Hippolytus of Rome (c. 170 – c. 235), while giving instructions for church gatherings, said "… let all the women have their heads covered with an opaque cloth, not with a veil of thin linen, for this is not a true covering." (4)

Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 220) wrote: “Throughout Greece, and certain of its barbaric provinces, the majority of churches keep their virgins covered. In fact, this practice is followed in certain places beneath this African sky. So let no one ascribe this custom merely to the Gentile customs of the Greeks and barbarians. Moreover, I will put forth as models those churches that were founded by either apostles or apostolic men. . . . The Corinthians themselves understood him to speak in this manner. For to this very day the Corinthians veil their virgins. What the apostles taught, the disciples of the apostles confirmed. I also admonish you second group of women, who are married, not to outgrow the discipline of the veil. Not even for a moment of an hour. Because you can't avoid wearing a veil, you should not find some other way to nullify it. That is, by going about neither covered nor bare. For some women do not veil their heads, but rather bind them up with turbans and woollen bands. It's true that they are protected in front. But where the head properly lies, they are bare. Others cover only the area of the brain with small linen coifs that do not even quite reach the ears.... They should know that the entire head constitutes the woman. Its limits and boundaries reach as far as the place where the robe begins. The region of the veil is co-extensive with the space covered by the hair when it is unbound. In this way, the neck too is encircled. The pagan women of Arabia will be your judges. For they cover not only the head, but the face also. . . . But how severe a chastisement will they likewise deserve, who remain uncovered even during the recital of the Psalms and at any mention of the name of God? For even when they are about to spend time in prayer itself, they only place a fringe, tuft [of cloth], or any thread whatever on the crown of their heads. And they think that they are covered! (5)

Origen of Alexandria (c. 185 – c. 253) wrote, "There are angels in the midst of our assembly … we have here a twofold Church, one of men, the other of angels … And since there are angels present … women, when they pray, are ordered to have a covering upon their heads because of those angels. They assist the saints and rejoice in the Church."

In the Didascalia Apostolorum, we find this: “ "Thou therefore who art a Christian [woman] … if thou wishest to be faithful, please thy husband only, and when thou walkest in the market-place, cover thy head with thy garment, that by thy veil the greatness of thy beauty may be covered; do not adorn the face of thine eyes, but look down and walk veiled; be watchful, not to wash in the baths with men." (6)

Further proof of the practice of the Early Christians comes from the walls of the Christian catacombs, where artistic depictions of women in prayer are wearing veils.

The mode in which the early Christians spent the Lord’s day is thus described by Dr. Jamieson in his Manners and Trials of the Primitive Christians (1839):

“Viewing the Lord’s day as a spiritual festivity, a season in which their souls were especially to magnify the Lord and their spirits rejoice in God their Savior, they introduced the services of the day with psalmody, which was followed by select portions of the prophets, the Gospels, and the epistles, the intervals between which were occupied by the faithful in private devotions. The plan of service, in short, resembled what was followed in that of the vigils, though there were some important differences, which we shall now describe. The men prayed with their heads bare, and the women were veiled, as became the modesty of their sex, both standing - a position deemed most decent and suited to their weekly solemnity - with their eyes lifted up to heaven and their hands extended in the form of a cross, the better to keep them in remembrance of Him…”

Let us continue with the words of the Church Fathers:

8. St. John Chrysostom (c. 347 – 407) thought that St. Paul, in admonishing women to wear a covering "because of the angels", meant it "not at the time of prayer only, but also continually, she ought to be covered”:

“Well then: the man he compelleth not to be always uncovered, but only when he prays. "For every man," saith he, "praying or prophesying, having his head covered, dishonoureth his head." But the woman he commands to be at all times covered. Wherefore also having said, "Every woman that prayeth or prophesieth with her head unveiled, dishonoureth her head," he stayed not at this point only, but also proceeded to say, "for it is one and the same thing as if she were shaven." But if to be shaven is always dishonourable, it is plain too that being uncovered is always a reproach. And not even with this only was he content, but he added again, saying, "The woman ought to have a sign of authority on her head, because of the angels". He signifies that not at the time of prayer only but also continually, she ought to be covered. But with regard to the man, it is no longer about covering but about wearing long hair, that he so forms his discourse. To be covered he then only forbids, when a man is praying; but the wearing of long hair he discourages at all times.” (7)

St. John Chrysostom also believed that to disobey the Christian teaching on veiling was harmful and sinful. He says:

"… the business of whether to cover one's head was legislated by nature (see 1 Cor 11:14–15). When I say 'nature', I mean 'God'. For he is the one who created nature. Take note, therefore, what great harm comes from overturning these boundaries! And don't tell me that this is a small sin."

In a sermon at the Feast of the Ascension, he spoke again of both the angels and the veiling of women:

“The angels are present here . . . Open the eyes of faith and look upon this sight. For if the very air is filled with angels, how much more so the Church! . . . Hear the Apostle teaching this, when he bids the women to cover their heads with a veil because of the presence of the angels.”

9. In a letter, St. Jerome (c. 347 – 420) noted that a hair cap and prayer veil was worn by Christian women in Egypt and Syria. He says of them that they "do not go about with heads uncovered in defiance of the apostle's command, for they wear a close-fitting cap and a veil.” (8)

10. St. Augustine (354 – 430) weighs in about the head covering in a letter to his friend Possidius, who was Bishop of Calama. Possidius had asked Augustine some questions about women’s attire, and in his part of his response Augustine said: "It is not becoming, even in married women, to uncover their hair, since the apostle commands women to keep their heads covered." (9)

11. St. Cyril of Alexandria (c. 376 - 444) commenting on First Corinthians, wrote: “The angels find it extremely hard to bear if this law [that women cover their heads] is disregarded.”

We also have early councils, synods, and popes speaking on head coverings.

12. At the council of Autun in 578, it was mandated that a woman cover her head in order to receive the Eucharist. As a result, a white veil or coif called velamen dominicale (which I believe translates to Sunday covering) was worn by females at the time of receiving the Eucharist during the 5th and 6th centuries. (10)

13. In 585, the Synod of Auxerre (France) stated that women should wear a head-covering during the Holy Mass. (11)

14. In 743, the Synod of Rome declared that: "A woman praying in church without her head covered brings shame upon her head, according to the word of the Apostle.” (12) This position was later supported by Pope Nicholas I in 866. 13

All of this gives evidence that St. Paul’s command about head-covering was taken seriously by the Church for centuries.

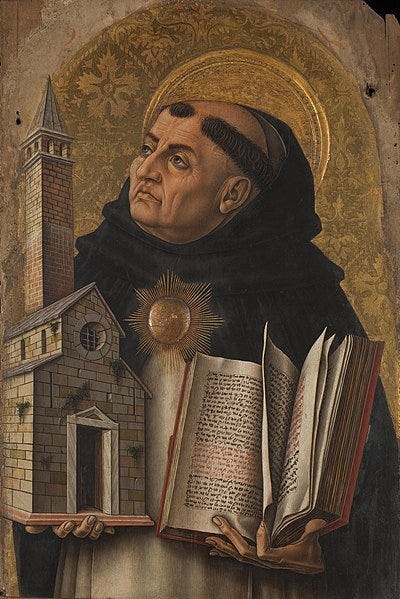

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225 - 1274)

I would like to give special care to the words of St. Thomas Aquinas because of his elevated place in the Church. Among theologians, the Church especially singles out St. Thomas. The Church has never ceased to approve and recommend him.

St. Thomas continues and develops the works of the Fathers, especially that of St. Augustine. He was a theologian, contemplative, and mystic whose principal source is Tradition and Sacred Scripture. The Church has recognized in St. Thomas’ writings the exact expression of Tradition.

Here I provide a few citations of how highly the Church regards him:

“His life was holy and his teaching could not but be miraculous … for he illuminated the Church more than all other Doctors. A man who spends one year with his books gets farther than if he were to spend his whole life studying the teachings of others.” – Pope John XXII (1316 -1334) (14)

“Furthermore, we command you to follow the doctrine of the Blessed Thomas, which is true and Catholic; strive with all your powers to master it and make it known.” – Bl. Urban V (1362-1370) (15)

“That from henceforth no master or reader of this same College of St. Denys shall read, teach and explain anything to the students in schools and faculties of the said College, particularly in theological matters, other than as taught by St. Thomas Aquinas.” – Pope Benedict XIV (1740-1758) (16)

“Particularly in philosophical and theological matters, as we have already said, no one turns aside from Aquinas without great detriment. Following him is the safest path to profound knowledge of divine things … His golden teaching illuminates the mind with its splendor. His life and intellect lead us to the profoundest knowledge of divine things without any danger of error.” – Pope St. Pius X (1903 - 1914) (17)

“It is evidence that those who depart from Thomas, if they pursue their path to the end, part company with the Church.” – Pope St. Pius X (1903 - 1914) (18)

“...professors should denote all their labors to the intellect, teaching and principles of the Angelic Doctor, and should persevere in it in holiness.” — 1917 Code of Canon Law, Canon 1366

What, then, did this good and holy Doctor of the Church say of our topic at hand?

In his commentary of 1 Cor, St. Thomas Aquinas said this about head coverings for women:

"The man existing under God should not have a covering over his head to show that he is immediately subject to God; but the woman should wear a covering to show that besides God she is naturally subject to another."

St. Thomas further explains St. Paul’s statement “because of the angels” in two parts:

“Then when he says, because of the angels, he gives a third reason, which is taken on the part of the angels, saying: A woman ought to have a veil on her head because of the angels. This can be understood in two ways: in one way about the heavenly angels who are believed to visit congregations of the faithful, especially when the sacred mysteries are celebrated. And therefore at that time women as well as men ought to present themselves honorably and ordinately as reverence to them according to Ps 138 (v. 1): “Before the angels I sing thy praise.”

“In another way it can be understood in the sense that priests are called angels, inasmuch as proclaim divine things to the people according to Mal (2:7): “For the lips of a priest should guard knowledge, and men should seek instruction from his mouth; for he is the angel of the Lord of hosts.” Therefore, the woman should always have a covering over her head because of the angels, i.e., the priests, for two reasons: first, as reverence toward them, to which it pertains that women should behave honorably before them. Hence it says in Sir (7:30): “With all your might love your maker and do not forsake his priests.” Secondly, for their safety, lest the sight of a woman not veiled excite their concupiscence. Hence it says in Sir (9:5): “Do not look intently at a virgin, lest you stumble and incur penalties for her.”

According to St. Thomas, St. Paul is speaking of the angels in the invisible hierarchy that are present in church and who take offense at any signs of irreverence in the presence of God. But he also interprets the angels as representing the holy priests, since they act as angels as the ministers of the divine to the people, and women then veil before these representatives of Christ in Church as a sign of reverence as well as for the sake of avoiding any potential stirring of concupiscence.

Why cover the head? What does it mean?

According to St. Paul, the veil is a visible sign that the woman is under the authority of a man. The symbolism of the veil takes that which is invisible, the order established by God, and makes it visible. Veiling carries with it a certain objective reality, an outward symbolism of the virtues of humility and obedience in response to apostolic exhortations. For this reason, many women refuse to wear a head covering, for they refuse to acknowledge that woman is under the authority of man. This biblical notion is so repulsive to some women that they not only oppose it for themselves but encourage other women to discard their veils as well, in the name of liberation.

However, lest we think it is only a sign of her ordained place beneath man, we should also look at the other reasons why women personally choose to wear veils:

Modesty

Humility: an external sign of a woman's interior desire to humble herself before God, and a public proclamation of her desire to submit to the will of God.

A visible reminder of the spousal relationship between the Church and Christ. The Church is the Bride and Christ is the Bridegroom. Women symbolize the Church (the Bride) when she veils, this is a visible reminder of the submission of the Church to Christ.

A sign of the dignity inherent to a woman. She, and not man, has the potential to receive life within herself. It is an honor to wear a veil as part of female dignity.

In imitation of Our Lady, the perfect model of all virtues.

As an exterior witness to belief in the Real Presence.

Practically speaking, the veil can serve to mitigate temptations toward vanity and limit distraction during public worship.

A Special Consideration on Modesty

In St. Paul's first epistle to Timothy, he says: “Therefore I desire that men pray everywhere, lifting up holy hands, without wrath and doubting; in like manner also, that women adorn themselves in modest apparel, with propriety and moderation, not with braided hair or gold or pearls or costly clothing..."

Concerning this verse, St. John Chrysostom comments:

"But what is this modest apparel? Such attire as covers them completely and decently, not with superfluous ornaments, for the one is becoming, the other is not... Do you approach God to pray with braided hair and ornaments of gold? Are you coming to a dance, to a marriage, to a merry procession? ... You have come to pray, to supplicate for pardon of your sins, to plead for your offenses, beseeching the Lord, and hoping to render him propitious to you ...For is it not acting to pour forth tears from a soul overgrown with extravagance and ambition? Away with such hypocrisy! God is not mocked! This is the attire of actors and dancers, living on the stage. Nothing of this sort becomes a modest woman, who should be adorned with shamefacedness and sobriety..." — St. John Chrysostom, Homilies VIII and IX on I Timothy II

It was the teaching of St. Paul (and also of St. John Chrysostom) that women should come to the church focused on the task at hand: to pray. There should be a modest and sober demeanor inside this holy place where such a holy thing is happening.

St. Paul also teaches us in Philippians 4:5 to: “Let your modesty be known to all men.”

A woman's hair is her glory and when she covers it, it is an act of humility and modesty. Hopefully as she covers herself, her presence "decreases," and His increases.

My personal favorite symbolism is the bridal veil. The woman's veil is protecting the precious purity inside. At the marriage, when the bridegroom lifts the veil of his bride, it is literally the veil being lifted between them and allowing him access. From that point on, she is for her husband only, and the veil of a married woman symbolizes their exclusive union. No man but her husband has the privilege of moving beyond that veil. It's reserved for him. This is why some women choose to cover all of their hair when in the presence of men who are not their husbands: it is a physical symbol of their fidelity to their husband; the beauty of their hair is a privilege for him alone.

How Head Coverings Have Changed

In the early period of the medieval age, women wore their hair loose but covered, with married women being required to cover all of their hair. No respectable woman would have thought of leaving her home with her head bare, and this included all social classes (although the coverings of the poor and the rich were different). Head coverings during the medieval ages changed from long veils to pointed caps to rolled bonnets. They took the forms of wimples, veils, scarves, or loose shoulder capes. From the 10th to 14th century, neck-covering wimples were in style. In the 14th and 15th century, tall, canonical headdresses with veils attached were used. In the 15th and 16th century, low hoods and caps. (19)

After the Protestant Reformation, the Reformers kept the tradition of head-coverings for women in their churches. Martin Luther, John Calvin, John Knox, John Wesley and Roger Williams all held that women should wear coverings during public worship. For all of them, this was based on the Scriptural injunction of first Corinthians.

There are still some Protestant denominations that hold to head-covering practices in our modern day, and a few do so in a very strict sense. Mennonite head-coverings tend to be sheer, white, bonnet-style caps worn at the back of the head. Hutterites wear a black tiechl, similar to a kerchief. (20)

Through history, it would seem that head coverings became part of fashionable attire. As fashions change and trends come and go, the style and appearance of the coverings changed from time and place. An example of this is the 19th century cap, an imminently stylish accessory which ladies of the age were continually reinventing through lace, ribbons, and trimmings. In the Victorian Era of British history, we find numerous possibilities for covering the head. Bonnets and caps ranged from plain and simple to elaborately embellished with frill and flounce.

As the form and style of head coverings changed over time, it is thought that their religious significance was forgotten and they became more and more a societal norm of acceptable and respectful behavior rather than a religious mandate. In other words, to be in church without a hat was not necessarily thought of as something sinful but as something poor in taste and against proper etiquette. This would explain why veils became caps and bonnets, caps and bonnets became fashionable hats, and fashionable hats were eventually abandoned. The spiritual significance had been lost to fad.

This exemplifies the danger of attaching a purely worldly significance to the practice of head covering: the supernatural aspect and theological meaning is quickly forgotten in favor of whatever is in vogue at a particular time.

The Controversial Mantilla

The most common type of veil seen in Catholic Church’s today is a small, triangular, lacy veil known as a mantilla. But did you know this type of veil has a controversial history?

The origins of the mantilla come from the warm regions of Spain, coming into use in the late 1500s. Mantillas are lightweight, ornamental, made of lace, and often worn over a high comb called a peineta. The ones we see today are shorter and without the comb.

It appears that the mantilla was an ornamental piece of a woman’s wardrobe, and it made its way into the Mass as a cultural adaptation of the required head coverings. From Spain, the mantilla spread to Central America with Catholic missionaries.

In the 19th century, Bishop Nicolás García Jerez (1757 - 1825), Bishop of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, mandated that mantillas be opaque and not made of transparent lace. He said that women who covered their head with a gauze mantilla or clear muslin did not contribute to modesty and decorum but only served to call attention to themselves as an idol of prostitution and a stumbling block. He ordered that women who chose to continue wearing transparent mantillas be thrown out of the Church and excommunicated. (21) This was based on the early Church's apostolic tradition which specified that head covering should be observed with an "opaque cloth, not with a veil of thin linen.”

Queen Elizabeth II (1833-1868) greatly popularized the use of the mantilla, but its popularity diminished after her abdication in 1870. By 1900, the use of the mantilla became limited to church, bull fighting, holy week, and weddings.

Today, the little mantilla has become the most common form of veil within traditional Catholic communities in the West.

When did the Church abandon this practice?

Women praying in church with their heads covered has always been in place as part of Church law and tradition. It was universally practiced and in force everywhere in the Church throughout her whole history, all the way up to its inclusion in the Code of Canon Law of 1917:

Canon 1262

1. It is desirable that, consistent with ancient discipline, women be separated from men in church.

2. Men, in a church or outside a church, while they are assisting at sacred rites, shall be bare-headed, unless the approved mores of the people or peculiar circumstances of things determine otherwise; women, however, shall have a covered head and be modestly dressed, especially when they approach the table of the Lord.

What changed? It was in the wake of the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) that the Roman Catholic Church discarded this ancient practice and removed its obligation on women. The 1960’s were a time of revolution. Feminism and the sexual revolution were raging, and the pervasive ideologies of the revolutionary culture led to the decline of the use of head coverings in America and Western Europe.

In the United States, the National Organization for Women released this "Resolution on Head Coverings" in 1968:

“WHEREAS, the wearing of a head covering by women at religious services is a custom in many churches and whereas it is a symbol of subjection within these churches, NOW recommends that all chapters undertake an effort to have all women participate in a "national unveiling" by sending their head coverings to the task force chairman immediately. At the Spring meeting of the Task force on Women in Religion, these veils will then publicly be burned to protest the second class status of women in all churches.”

NOW acknowledged that head covering was the normative practice of females in Christian churches and initiated a "national unveiling" campaign in which head coverings were collected and then publicly burned in protest of the "second class status of women in all churches".

While the sexual revolution raged on outside the Church, a liturgical revolution raged on within. It was in 1970, after the dramatic changes of the Second Vatican Council, that the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith released a declaration titled Inter Insigniores. Paragraph 4 of this document spoke specifically of the prescriptions of St. Paul concerning women and the “difficulties that some aspects of his teaching raise in this regard.” It was declared that:

“... these ordinances, probably inspired by the customs of the period, concern scarcely more than disciplinary practices of minor importance, such as the obligation imposed upon women to wear a veil on their head (1 Cor 11:2-16); such requirements no longer have a normative value.” (22)

Shortly after, in 1983, the second and current codification of canonical legislation for the Latin Church came out (aka, a new code of canon law.) The canon about head veils from the 1917 code was not re-issued in the new version.

Canon 6 of the current code states that all subsequent laws that are not reissued in the new code are abrogated. Therefore, the Church law regarding head coverings for women was officially abrogated in 1983.

In other words, after an almost-2,000 year history of head covering as law and tradition, the Church conformed to the feminist agenda of the age by calling head coverings “of minor importance.” This flies in the face of everything the Church held and taught previously. Despite Jesus’ command to not be “of the world,” and Romans 12:2 telling us “be not conformed to this age.” What was truly “inspired by the customs of the period” was the removal of the veil, which was pushed for by a feminist agenda.

Is it any surprise that women today have abandoned the tradition of veiling when some of the greatest meanings of the veil are modesty, humility, and obedience? When women refuse to wear the veil, they are refusing to concede to everything it represents.

Although the Church determined that covering no longer has “normative value,” there was never any prohibition against wearing a veil. Women are not forbidden from voluntarily choosing to cover, if they wish.

The Russian Orthdox Church

The Russian Orthdox Church has not removed its requirement of head coverings for women (although other Orthdox churches have made it optional). Patriarch Kirill, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, answered in an interview, “Why do we need headscarves in churches? Because people should think of prayers while in church. When a beautiful woman comes in (with her hair uncovered) it naturally attracts attention – and distracts from the holy service.”

In my research, I’ve come across the writings of Orthdox priests and several of them advocate for women to wear head-coverings all of the time, not just inside a church. This is based on the teachings of St. John Chrysostom who preached that head coverings were to be worn continually. One such priest who advocates for this practice is Fr. Patrick, who writes on his blog:

“The head covering is not merely for the wearers humility and obedience, it quietly bears testimony before all, to lead all to obedience and humility. Because obedience to God is due at all times, head coverings are also worn at all times, particularly in the presence of others, even in the home. Women remain covered to show the need of our continuing obedience to share one will with God.”

He goes on to explain the type of head covering that he believes is best based on Patristic sources:

“A head covering is supposed to cover the head fully as being completely under obedience to God. Thus, head scarves are appropriately wrapped around the head as are also many eastern forms of head coverings as used in Muslim, Jewish or even Hindu cultures. A small hat on top of the head, particularly one that is decorative, is not as appropriate, although it is better than being without. Being without, in terms of its symbolism, is a sign of rebellion against God and of self-will, setting oneself as ruling like God if not done according to the will of God.”

Similarly, Fr. Basil Rhodes, who wrote his Master of Divinity thesis in 1977 on the veiling of women in I Cor. 11, agreed with St. Chrysostom:

“The veil can be the constant symbol of the true woman of God...a way of life...a testimony of faith and of the salvation of God, not only before men, but angels as well.”

Although the Orthodox faith differs from Catholicism, I included this here because as far as I can tell, the Russian Orthodox faith is the only one that has continued the tradition of head-coverings for women in its most pure form, that is, the closest to the intentions of the early Church Fathers who described a covering as a veil that covers down over the neck for modesty’s sake.

What have we lost and what are the consequences?

By abandoning the veil, women have abandoned all the symbolism that goes along with it.

When we see a veiled nun, we know that she is a religious who consecrated her life to God. Similarly, when we enter a church and see veiled women, their veils say something to us. They speak to us of modesty and humility and redirect our mind to God. When a woman puts on a veil, it is an act of obedience, humility, modesty, and piety. It can help her reorient herself to God.

When a woman dons a cover as she enters a church, she is making a bold statement. A woman who covers becomes a silent witness to Jesus Christ. In a humble spirit, the head is covered with the intention of giving great reverence to Our Lord, Who is truly present in the Blessed Eucharist. For human beings, this is a visible reminder that we are in a sacred place and it directs our thoughts, intentions and desires to Jesus.

When we treat the liturgy and the Eucharist in a casual manner, we run the risk of adopting a casual attitude towards the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and the reception of the Sacraments. Since the Church has cast aside all its previous reverent practices toward the Eucharist, belief in the Real Presence has dropped dramatically. Only 30% of Catholics believe in the Real Presence. (23)

The exterior practice of covering the head is a physical action and visible reminder of what we believe about the Eucharist. Because we are made of both body and soul, and the two are intimately connected, and what we do with our physical body matters. With the right interior disposition, our exterior dispositions (such as our posture, behavior, and attire) can augment our faith. Of course, our exterior practices should always be motivated from the right interior attitude: that is, love of God. If we put on an exterior display of virtue and piety while hiding a rotting interior, this makes us no better than the hypocritical Pharisees that Our Lord condemned. But when our exterior practices are animated by the proper interior disposition, then our exterior worship is in harmony with our interior belief, and they become respectful, submissive acts of piety directed to God with love.

Loomis, L. (1916). The book of the popes (Liber pontificalis) I-. New York: Columbia University Press.

Source: Irenaeus, Against Heresies, Book 1, 8:2, cited in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, A. Cleveland Cox, ed., (U.S.A: The Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1885), I:327.

Clement, The Instructor

The Apostolic tradition of Hippolytus

Tertullian, The Veiling of Virgins

Gibson, Margaret Dunlop (1903). The Didascalia Apostolorum in English. C.J. Clay. pp. 9–10.

Schaff, Philip (1889). A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church: St. Chrysostom: Homilies on the Epistles of Paul to the Corinthians. The Christian Literature Company. p. 152.

Jerome, Letter CXLVII:5, cited in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Philip Schaff, ed., (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Co., VI:292.)

(McClintock, John; Strong, James (1891). Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature. Harper & Bros. p. 739)

Schmidt, lvin (1989). Veiled and Silenced. Mercer University Press. p. 136.

Synod of Rome (Canon 3). Giovanni Domenico Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum Nova et Amplissima Collectio, p. 382

Schmidt, lvin (1989). Veiled and Silenced. Mercer University Press. p. 136.

Acta sanctorum, vol 1 martii, 681-682 = Ramirez De auctoritate doctrinali S. Thomae, p. 36.

Bull Laudabilis Deus = Ramirez, op. Cit., p. 37

Bull of Approbation of the College of St-Denys = Ramirez, op. Cit., pg. 40

Motu proprio Praeclara

Letter to Rev. Fr. Pegues, cited in Ramirez, op. Cit, p. 122

Rosalie's Medieval Woman - Veils and Wimples (rosaliegilbert.com

Castañeda-Liles, María Del Socorro (2018). Our Lady of Everyday Life: La Virgen de Guadalupe and the Catholic Imagination of Mexican Women in America. Oxford University Press. p. 238.

Declaration on the Question of Admission of Women to the Ministerial Priesthood (vatican.va)

This was really interesting! Thank you for sharing!