In April, 2009, we were living in Okinawa, Japan and I was 38 weeks pregnant with my second child. One afternoon, while my husband attended a company work party, I had arranged to meet up with some friends. However, my plans were disrupted when the hospital notified me of an "abnormal" result on my recent ultrasound, and they requested that I come in immediately. Tending toward a more "natural" mind-set, I was skeptical of the doctor's alarm and thought it might be an overreaction, likely unwarranted. I was already at the end of the pregnancy; the baby was full-term; and the whole pregnancy had been entirely healthy and uneventful. Briefly, I even contemplated ignoring the call and proceeding with my day. But ultimately, I decided to go to the hospital.

Upon my arrival at the hospital, I was informed that my amniotic fluid levels were dangerously low. I spent the entire day there as they conducted tests and ultrasounds, repeatedly measuring, until they concluded that the situation was dangerous, and induction was necessary. They didn't start the pitocin until midnight, and it dripped all night long, until 7:00, at which point I had zero dilation. After enduring seven hours of intense pitocin-induced contractions without any sleep, I was deemed a "failed induction" and was told I would be monitored for another two hours before being discharged. Those two hours passed uneventfully. But at 9:00 am, just when I was preparing to leave, the doctor decided to check my cervix once more, and surprisingly, I had dilated to a 5.

I endured six hours of the most intense and challenging labor I have ever faced. Roughly six hours later, around 3:00 PM, I delivered my six-pound, seven-ounce baby into the doctor's waiting arms. Happy that the ordeal was behind me, I lay back on the hospital bed and closed my eyes in relief.

The labor had been exhausting, and since I hadn't slept in days, I didn't immediately notice that something was amiss. Soon enough, I began to wonder why they hadn't laid my daughter on my chest, and that's when I saw them quickly taking her across the room. I wasn't concerned yet because I hadn't grasped the level of danger she was in.

It was then that my doula took both of my hands into hers and told me to look her in the eyes. She was speaking to me, but I wasn’t hearing the words. A firm sense of dread had settled into my stomach. It was dawning on me that something was very wrong. I looked away from her and saw them rush my baby out of the room. There was panic and tension, with much of the staff running in a hurry. I saw my husband across the room, looking panicked, and so I shouted at him, "Go with her!" He disappeared out the door behind them.

"She's having some trouble breathing," they told me. "We're taking her to the NICU. She just needs a little extra help." I settled a little bit then, feeling a sense of comfort, and being confident that she'd be back shortly. She just needs some oxygen, I thought.

But then, my husband came back into the room, looking ill. I sat up anxiously and asked, "is she okay?" He looked at me with a look of dread and a quivering lip, then broke down into sobs. It felt like a rock had slammed into my stomach in that moment. I thought for sure she was dead.

But, she wasn't, thanks be to God! The doctor on shift had tried and tried and tried to get the breathing tube down her throat, but just couldn't. My husband couldn't bear to watch anymore, the panic was too much, and he left the room. But they had paged another doctor, and the story I was later told was that she was sleeping in her quarters across the street when she got the call. She had run out the door in her pajamas and raced to the NICU as fast as her legs would carry her, and she successfully intubated. Her name was Doctor Pole, and she saved Anja’s life.

My next clear memory is being in the recovery room, having been moved from the delivery room. Everything felt wrong; it was as if the earth had simply stopped spinning. There I was, in a small hospital room on a tiny island, grappling with the reality that just a day ago, I was pregnant and anticipating the arrival of my second child, but now I was facing the possibility that she might not live.

When the doctor came in to discuss the situation, she informed us that our daughter exhibited multiple signs of a chromosomal disorder. She indicated that it was likely a trisomy index - either 13, 18, or 21. She explained that the most favorable outcome would be Trisomy 21, also known as Down Syndrome. However, she cautioned that there was a chance our daughter's condition might be "incompatible with life," advising us to "prepare for the worst."

My husband returned home to care for our two-year-old son. I had no choice but to stay in the hospital by myself. As soon as I had permission to visit the NICU, I hurried as quickly as my body allowed, dragging my pitocin drip behind me. Despite the nurses' insistence on using a wheelchair, I chose to walk.

It was the first time that I had ever seen a newborn in an incubator, hooked up to several beeping machines, with various wires and tubes. I'd never seen anything like it, it looked so unnatural and surreal. I had carried this baby within me for nine months, filled with countless happy expectations for her arrival, yet each one was shattered as effortlessly as dropping a glass to the ground.

I reached my hand inside the box and stroked her cheek. But it was more than I could bear: this tiny, helpless baby inside a plastic box, unable to be held by her mother. I wondered, does she feel sad to be alone? Does she wonder where I am and why I am not holding her? Does she know how much I love her? "I'm here," I whispered. "I'm here and I do love you," I sobbed. I could not stop crying. I had to leave the room.

But sitting in the hospital room was no better. It was the middle of the night, and I was alone, flipping mindless through TV channels. Occasionally a nurse would come in to check my bleeding and massage my uterus. I pumped breastmilk every couple of hours and delivered the bags to the NICU. After a completely sleepless night, I went back to the NICU to see her again. This time, the nurses were bustling with excitement. "Anja knocked her breathing tube out!" they said. "And we didn't need to put it back in because she's breathing on her own!" I rushed to the incubator and pressed my face against the plastic. There was no tube down her throat. Although she had a nasal cannula for oxygen, her chest was rising and falling without the assistance of a machine.

I was finally able to hold her, and holding her in my arms for the first time was an incredible source of comfort and strength. Holding her little body close to mine made me feel like everything might be okay after all. It was the first time that I had felt a sense of calm and peace since she had been born. But then, I had to lay her back into the box and leave the room, and it brought a sense of dread again. It just felt wrong to leave my baby, it went against all of my instincts. I wanted to hold her and take care of her, but her needs were beyond what I could give. I had moments of courage and hope, but moments of heavy despair, too.

It was later that night that she finally latched on and I was able to breastfeed her for the first time. She had some trouble, but did manage to nurse for a little while. In the moment it seemed like a great triumph, but unfortunately, the first time she nursed was also her last. Breastfeeding proved too difficult for her - she was unable to manage sucking, swallowing and breathing all at the same time. Because she could neither breastfeed nor drink from a bottle, a nasogastric tube had to be placed. We encouraged her to suck on a pacifier so she wouldn't lose her ability to suck.

Now that her eyes were open and she was alert, I was getting to know my daughter. She had a head full of dark, black hair, and smooth, white skin. I kept thinking of how the doctor had told us that she likely had Trisomy 18, that her case was “so typical,” that they were so sure that's what the test results would bring back. With this on my mind, I knew there was a real possibility that I had only a matter of weeks with my baby before she passed on. Never before had I so closely studied each hair on a baby's head, or nuzzled my nose against a baby's cheek wondering if it would be last time, or watched each breath wondering how many she had left.

We were quick to call for a Military chaplain who was able to come in and baptize her. Just in case.

It took two weeks for the test results to come back, and they shocked the doctors: there was no trisomy index. Anja did not have trisomy 13, 18, or 21. This was wonderful news, but it also left us wondering what then could be causing all her various medical issues?

As the long days passed in the hospital, it seemed like there were only more pieces added to the puzzle. The doctors were bewildered. Their speculation about what it could be was always wrong, which became increasingly aggravating as they sought treatments that made no difference. I can't count how many times we were told "maybe this will help," and then whatever they did made no difference at all.

The first three weeks of her life were a blur of tests, scans, lab work, antibiotics and increased oxygen needs. They discovered that she had swollen vocal cords, which made them think she had reflux, and so they put her on zantac. And then, maybe the reflux was getting into her lungs and causing her breathing problems, so another antibiotic, just in case. Yet, nothing helped her breathing issues at all, and in fact, they only got worse. At one point, they thought she had a tracheoeseophageal fistula. "It would explain everything," they said. But she didn’t. Back to square one.

At three weeks old, she deteriorated and was placed back on the ventilator. It seemed as though all her previous "progress" had been for nothing. The uncertainty of why she required a ventilator was frightening, and it was heart-wrenching to watch her be sedated to ensure she wouldn't knock the breathing tube out.

Finally, the doctors admitted there was nothing more they could do for her at this particular hospital. They simply did not have the right specialists to help her. They informed us that were sending another baby from the NICU on an emergency flight to Hawaii that afternoon, and they wanted Anja on that flight as well.

We had only a moment's notice to pack a few essentials and race to the air force base to catch our flight. It didn't even sink in at the time, but I was leaving behind my home and all of my possessions. I would never return to Japan again. (And we had no idea that by the time my husband came back to pack up our belongings, they would have all completely molded in the high Okinawan heat and humidity. We would end up losing all of our possessions and starting life over).

But we didn’t know that then. For now, we were on an air force plane, crossing over the Pacific Ocean, headed from one island to another. During the flight to Hawaii, Anja required a blood transfusion.

Once we landed, things moved quickly. Anja had taken a serious turn for the worse and now required a small heart surgery. Her ductus arteriosus failed to close after birth (a congenital disorder known as patent ductus arteriosus, or simply PDA) and she required a PDA ligation to close it. The doctors were so confident that her poor weight gain and her ventilator/oxygen dependency would improve after this surgery.

The surgery was successful, and within three days post-procedure, she was able to be removed from the ventilator. However, she continued to require supplemental oxygen via a nasal cannula. Her chest was still pulling pretty heavily when she breathed, and her oxygen saturation dropped dangerously low if she cried. She was also unable to swallow, which the doctors attributed to inflammation caused by intubation. They anticipated that she would start swallowing once the swelling subsided. But for the time being she was still requiring a feeding tube down her nose, as she was still completely unable to feed from either a bottle or the breast.

After her surgery, since she was doing a little better, she was able to be examined by a pediatric orthopedic surgeon. Anja had more problems than just her breathing and feeding issues— but those were obviously prioritized. The orthopedic surgeon ordered x-rays of her feet, which were severely deformed. She was born with a rare and severe foot deformity called rocker-bottom feet, or more formally, congenital vertical talus. He decided to put her feet in casts, to gradually stretch and reposition them into a more normal alignment. She required weekly re-casting to slowly move the bones into a better position. Despite the fact that it was only her feet that were affected, the casts came all the way up to her thighs, so both legs were entirely casted for 6 weeks.

There was another big problem with Anja’s bones: bi-lateral hip dysplasia. This is normally corrected with a brace, but the orthopedic surgeon said her case was too severe for the brace to do anything, and he expected her to need an open surgical reduction of her bilateral dislocated hips, probably around 8-10 months of age. This was going to be a big surgery, and it hovered ominously over us.

Due to her recent blood transfusion, the geneticist in Hawaii had to wait three weeks after the transfusion to draw blood and continue testing for genetic disorders. Eventually, blood samples were drawn and our hunt for a diagnosis continued.

Throughout all of this, Anja had a tendency to keep her muscles extremely stiff and tight. Her little hands were balled up into permanent fists, and it was a struggle to pry them open. As soon as they were released, they'd snap right back into tight fists. One of her nurses was experienced with baby massage and taught me some things I could do to help her muscles relax. I did it as often as I could, usually three times a day.

Shortly after her first surgery and being casted, an ENT doctor came in to see her and perform a bronchoscopy. What he discovered was that Anja's left vocal cord didn't move at all. The right vocal cord was compensating for this and going further than it needed to, thus never fully opening. In addition to the paralyzed vocal cord, Anja's glottis was overgrown. This left her with a space of about 1mm to breath and swallow through. This, the doctors thought, was surely the reason why she was struggling to breath, and why it was so difficult for her to swallow. This also explained why her voice sounded hoarse when she cried.

Within a week, Anja had surgery on her throat, to shave off the extra glottis tissue. The amount of tissue removed was only about 1.5 mm, yet immediately after the surgery we already noticed that her cry was stronger and louder. A week later, the doctor went in and took off a little bit more, because he hadn’t wanted to risk taking too much off the first time. Then, we anxiously waited for the swelling to go down to see if her breathing and feeding would improve.

At this point, the geneticist was leaning towards a diagnosis called Larsen's Syndrome, a mutation in the Filamin B gene, which helps control and guide proper skeletal development. However, this test came back negative.

Anja, now 2 months old, graduated from the NICU and went into the PICU. We got a whole new set of doctors with a fresh perspective. But unfortunately, we saw no improvement in either her breathing or her feeding. It was time to start thinking about more drastic measures, because it was evident that Anja could not live in the intensive care unit for the rest of her life. Hard decisions had to be made.

It was not an easy decision for me to make, but we did consent to a g-tube. I remember very well the feeling of complete hopelessness that came over me the day she had it inserted. It felt like "giving up" on her. It felt like saying, "You will never swallow food.” It is only in hindsight that I’m able to see that this was the best decision we could have made for her. But at the time, it felt awful, and that g-tube was one of the peskiest things I've ever had to deal with.

On July 11th, 2009, at the age 3 months, Anja was released from the hospital for the first time since her birth. She came "home," with supplemental oxygen and a g-tube, to a Fisher House. We had no real residence in Hawaii. Amidst the myriad of tests, surgeries, castings, and decisions at the hospital, we were drifting from one hotel to another. At first, we stayed at the Air Force lodging. Then we moved to a civilian hotel, off base. Then we moved to a hotel near Pearl Harbor. Then we finally moved into the Fisher House, free lodging for military families whose loved one is receiving treatment at the hospital. We shared the home with other patients and families who were struggling with their own profoundly difficult medical crises, and we found so much love and support there. That is where Anja came "home" to, the Fisher House.

When I look back on this time in my life, I don't see it as particularly bad, but it felt so stressful when I was enduring it. This is when my husband flew back to Japan to pack up our house, and I suddenly found myself taking caring for both my children alone, for the first time. I had been the mother of 2 children for a few months now, but I had never been alone with both of them. Add Anja's special needs on top of that, and I was pretty much a nervous wreck. I was learning how the Kangaroo pump worked (to give Anja her food), how to care for the g-tube, and how to juggle oxygen tanks and a pulse-oximeter with all the usual baby gear. At night, it was not the sound of a crying baby that woke me, but the sound of alarming machines. The pump would jam, or the bag of milk would be empty, or her oxygen would dip too low, or her heart-rate would rise too high. And that’s when the g-tube started popping.

The first time the g-tube popped, I had no idea what to do. I put medical tape over the hole and rushed to the near-by emergency room. The E.R. didn't have any g-tubes on hand, so they had to call Surgery. By the time a g-tube was sent down, the hole had already started closing. I didn't know that I should have left the tube in the hole to prevent it from closing, so that was my fault. This made it extremely painful for them to push the new g-tube in. All I remember is that I cried as much as Anja did.

A few days later, it happened again. I brought her back to the E.R. and they put a new tube in, but this time they filled the balloon with less water, thinking that perhaps it was popping because it was too full. A few days later, it happened a third time. I returned the E.R., and this time I was forced to speak with a social worker, because now my capability of caring for a special needs child was being brought into question.

The fourth and fifth time that the g-tube popped, I bypassed the E.R. and took her straight to the Surgery Department, because I was simply done dealing with the doctors in the E.R. who were clearly tired of seeing us over and over. They replaced it for me, and then they finally consented to sending me home with a box of g-tubes so I could replace it myself. It was after the seventh time that I demanded an x-ray, but it revealed nothing.

Finally, I found a doctor who had some common sense and solved the problem quickly and easily by switching her to a different kind of g-tube: a BARD, which is a solid piece that can't pop. The downside to this type of g-tube is that it is more difficult to remove, but that hardly seemed like a problem considering what I had just gone through, with seven g-tubes popping in just a few weeks. At last, the g-tube fiasco was over.

With Anja out of the hospital and my husband officially cleared from his base in Japan, it was time for a new assignment. They actually gave us the option of choosing our next home: we could stay in Hawaii, or we could go to San Antonio, TX. We decided to move to Texas because it was on the mainland and would enable family to visit and help us more easily.

The flight to Texas required a nurse travelling with us, for Anja's safety. We had to take a lot of medical equipment with us, including her oxygen tanks, pulse oximeter, and feeding pump.

On September 8th, 2009, we said goodbye to Hawaii.

Upon our arrival in Texas, we found ourselves in another hotel. Exhausted, we yearned for a place to call home, where we could settle into our new life with Anja. However, that hope was short-lived, as Anja's condition worsened within a week of our arrival. Her health drastically declined, leading to her admission to the PICU on September 15th, 2009, and she needed to be intubated again.

Because she was intubated, she also had to be sedated. If she was awake, she would thrash and try to knock the tube out (she was actually successful a couple times), so it became necessary to not only sedate her, but also sometimes to give her a paralytic. There are few things as nightmarish to a parent as standing beside your child's bedside when they are completely sedated and paralyzed.

I vividly recall one night when I visited her. As the nurse and I conversed beside the bed, Anja, upon hearing my voice, suddenly opened her eyes. She began to kick and attempted to spit out the breathing tube. Her eyes moved frantically, her expression one of terror, and she gazed at me as though pleading for help. The nurse increased her sedative dosage, and she drifted back to sleep. I have never felt such helplessness. As a mother, my role is to protect, yet in that moment, I was completely powerless to help my daughter.

Things escalated quickly. For the fourth time, Anja had a whole new medical team with yet another fresh perspective on her unusual case. This time, they were no-nonsense. Come October, the doctors flat out told us that Anja might die if we don't have a tracheotomy done. They didn’t know why she needed a trach, and they couldn't even guarantee it would help, but they saw no other option.

The neurologist wasn’t a very cheerful guy. He told us that she might have a debilitating, degenerative disease and that by giving her a trach we could only be unnecessarily pro-long her life, and it would be better to do nothing and "let her go" before she has to suffer anymore. But the pulmonologist completely disagreed, he said he wouldn't want to "pull the plug" on his child until they had all the answer, not just "maybes" and "what ifs" (God bless Dr. Palmer, he ended up being such a gift to our family!)

We were in the most difficult place we could imagine being. All I could do was pray for guidance and light from the Holy Ghost. I prayed that whatever decision we made would be in alignment with God's will. I thought of Christ's agony in the garden, and I felt for the very first time that I might have an inkling of what He meant when He uttered, "Father, if You are willing, remove this cup from Me; yet not My will, but Yours be done."

Sometimes, late at night, I would take a book to the hospital. Even though Anja was knocked out from the sedative, I would have the night nurse go through the gymnastics of nestling her into my arms, and then I would just sit and read for hours while holding her. Sometimes I'd read even read aloud to my sleeping baby. She was tangled in tubes and wires and smelled indefinitely of hand sanitizer. It was on one of those nights that I was overwhelmed with the desire to try with all my strength to do everything I could to save her life. I just knew that the trach our next step.

Just like with the g-tube, this was such a scary thing at first, and yet it was the best decision we could have made for her. We had a lot to learn: how to keep it clean, how to suction it, and how to change it. We also had to learn how to operate the home ventilator, such as what her settings were and what they meant, and what to do if the machine started alarming.

On December 2nd, 2009, she came home from the hospital - to a real home, because we really had a house by then. She came home with a trach, on a ventilator, and with a g-tube. She could not breath or eat on her own and required constant supervision.

Even though Anja was at home, she still required frequent doctor's appointments and consultations with various specialists. Her outings were limited to medical visits. With a ventilator, oxygen tanks, a pulse oximeter, a suction machine, and the usual baby necessities, it was a big undertaking to leave the house.

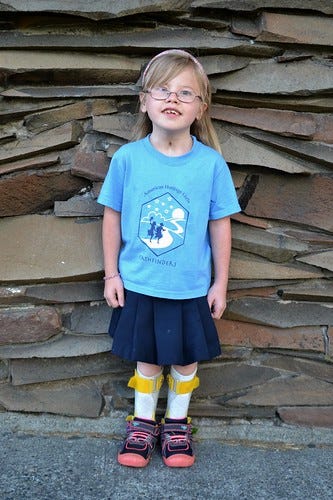

On December 14th, just 12 days after she had been released, we had an appointment. The photo below is exactly what we looked like that day we walked into the clinic.

When I handed the woman at the front desk my I.D. to check in, Anja's vent began to alarm. It alarms for many reasons and is not necessarily a cause for concern, but then her pulse oximeter also started alarming, which means that her oxygen saturation was dropping to a dangerous level. I glanced down and her saturation was dropping rapidly. 80. 70. 60. 50. I quickly popped the circuit off of her trach and started bagging her. After 4 or 5 breaths, she was still hovering at 55. I yelled at the lady at the desk to get a nurse. Everyone in the waiting room was gasping and someone screamed, "She's turning blue!" The nurses rushed in and pushed the stroller into a side room. The next thing I knew, there were at least 10 people crammed in this room and they are suctioning and bagging and asking me "What's wrong with your vent?” because there was no air blowing through the circuit. Well, oops. All that had happened was that the circuit had come disconnected from the vent. I felt like such a dummy. Once the circuit was reconnected to the vent, her stats returned to normal.

Unfortunately, I guess the little incident was some kind of premonition, because she ended up being re-admitted to the PICU that day for a suspected respiratory infection.

During this time, the geneticist was exploring a possible diagnosis of Hurler's Syndrome. The doctors seemed confident about this suspicion, because they found a strong indicator of it in her urine. This syndrome has a poor prognosis - it meant Anja would likely not live beyond her 2nd birthday - and we were scared.

However, once again, the results came back negative. No Hurler's Syndrome.

Around this same time, something odd happened. Very early on - at the first hospital -she had diagnosed with "horseshoe kidney.” The hospital in Japan made the diagnosis, and the hospital in Hawaii re-confirmed it. However, now we were now being told otherwise. They told us that her kidneys had a slightly abnormal shape to them, but the imaging studies showed that they are not joined together but clearly separated from one another.

After six weeks of caring for our daughter by ourselves, we were anxious to get nursing care started in our home. We qualified for this because Anja's needs required constant supervision, but the paperwork was slow. I don’t know why, but one way to speed up the process is to have an over-night stay at a nursing home. So in February, my husband's father drove Anja and I down to a city called Copperas Cove. Anja and I spent a restless night together in a run down little nursing home. By March, we had home-care nurses working in our home.

In addition to getting used to having our daughter home with all her special needs and adjusting to having nurses in our home 24/7, we also had to get used to Anja's monthly supply deliveries. Instead of a cute nursery, Anja's room was shelves and shelves of medical supplies that were constantly being delivered and re-stocked.

But having Anja home and having the nurses to help made life so much better for us. For the first time since Anja was born a year before, I was able to leave the house and make friends.

Anja still had no diagnosis, and the doctors had no idea if Anja was going to get better or worse as she aged, but Anja was a very happy baby who thrived immensely at home. She had a strong attachment to her dad, bonded with her brother, and came to trust and love her nurses as though they were family. But we had plenty of scary moments intertwined in our normal days. One day, we were at the hospital for an appointment when the ventilator malfunctioned. Another day, we were at the park when her trach plugged up and we hastily had to replace it with a fresh one. Once, her saturation dropped to 55 and I called 911 because the ambu bag wasn’t bringing it up.

At 15 months, Anja could barely hold her head up and was unable to sit up. She received both physical and occupational therapy regularly, in addition to speech therapy since she still could not eat solid food and did not make much sound. With the help of therapists and dedicated nurses, Anja made slow and steady progress. Her milestones were hit much later than "average,” but my heart still rejoiced every time. For every heartache we had endured in the past, we were now able to experience little joys as she took steps of progress forward. There were so many things going on, it’s hard to keep track of them all, but I do remember that she had to have her left eye patched because her right eye was lazy, and eventually she was prescribed glasses.

Eventually, Anja was able to eat pureed food and we were able to stop using the g-tube. Instead of pouring formula into a tube, I was cooking her real food and pureeing her meals. This was such an exciting and joyous time for our family as Anja was able to actually taste the food that she was eating for the first time, and her body was able to receive nutrition from REAL FOOD instead of supplemental formulas.

There was a specific therapy that helped her overcome her dysphagia (difficulty swallowing). It is called vital stim therapy. Two to three days a week, I would take her to a clinic and a speech therapist would put little electrodes on the exterior of her neck, right over the muscles used swallowing. For about 30 minutes, Anja would be given sips of water and bites of food while these muscles were electrically stimulated.

The year 2010 was marked with continual progress. She was surrounded with love, support and encouragement from her family, nurses, and therapists, and she thrived significantly. She even developed a way to be mobile despite not being able to crawl or walk: by scooting on her bottom and propelling herself with her arms.

As Anja grew older, she was gradually able to be taken off the ventilator. Soon enough, she managed to wean off the oxygen during the day and, in time, at night as well. Just as the doctors didn’t know why she needed a vent and oxygen, they didn’t know why she stopped needing them, except that her body grown bigger and stronger.

Anja was doing great. One by one her special needs were disappearing. She still didn’t talk much (so we learned sign language and that became her main method of communication) and she couldn’t walk, but other than that, she was a fairly normal 2-year-old.

Then, in July 2011, Anja was hospitalized again for the first time in a long time. She had a bowel obstruction and ended up requiring surgery and the removal of a portion of her intestines.

It had been so long since she'd be in the hospital that I'd kind of forgotten what it felt like. I was confronted with the reality that my child is not like other children, and she has to suffer and endure sad and painful things more often than the average child.

After she was discharged and home again, Anja started learning how to walk with a walker. This was such a beautiful thing to witness. She was given AFO braces with SMO inserts to help her stability. She practiced every day.

But just a few months later, at the end of October, we recognized the early signs of another bowel obstruction and didn't hesitate to take her in. This time, scar tissue from her previous surgery had grown and wrapped around her small bowel several times. They did an emergency surgery immediately, because it was starting to effect her pancreas which could of led to shock and seizures if not treated. The good news is that we caught this before blood supply was lost to the obstructed portion of the bowel, so no bowel had to be removed. They simply cleared the scar tissue.

We had always planned on Anja having a major surgery on her hips at some point in her life, before her second birthday. Now she was well past 2 years old. They had said they would only do one side at a time, so there was going to be two surgeries over the course of a month, with a six-month expected recovery. The ortho-surgeon in Texas, who had picked up her case, told us that he wanted to wait until Anja was bigger to do the surgery. We actually had the surgery scheduled twice in the past, but both times he called THE DAY BEFORE the surgery to tell us he was cancelling the operation. His reasoning was always "wait until she's older."

I finally requested a consult with a second doctor to get a second opinion. Her findings were that Anja's body was compensating for the dislocations and she had virtually no hip sockets at all anymore. She said Anja's surgery would now create SIX SEPARATE SURGERIES over the course of an entire year. They would have to shave off the top of each femur, create a socket, and reduce the femur into the socket. But there was a possibility it could pop back out, or worse, that Anja could lose blood flow and be paralyzed.

In the end, the doctor, my husband, and I all agreed that it would not be in Anja's best interest to have this surgery. So, she lives now with dislocated hips, and will for the rest of her life. This second doctor also told us that Anja had a 10 degree curve in her spine that was likely to get worse. We were told she may walk, or she may not. We were told she would likely be wheel-chair bound by the time she was a teenager or young adult.

Our next adventure was getting rid of the g-tube. Remember the BARD?

By March 2012, Anja was eating solid food - fully chewing and fully swallowing without any difficulty. Our g-tube days were over. She had been eating pureed food for some time, but it was kind of funny how we discovered that she could chew and swallow solid food. The Army relocated us to Washington, so our belongings were packed up and we drove our mini-van from Texas to Washington, with three little ones in tow. Our children were ages 5, 3, and 1. Anja was sitting in the back seat next to her 5-year-old brother. When we stopped for gas, I went to get Anja out of her car seat and I found her holding a bag of potato chips and eating them. I panicked a little bit at first, but then quickly realized that she was chewing and swallowing them without a problem. “How did she get these chips?” I asked. “I gave them to her!” My 5-year-old son said.

Shortly after we arrived in our new house, I made the kids grilled cheese sandwiches for lunch. I cut the sandwich in half and gave it to Anja. Sure enough, she was able to eat it without problem. So, Anja’s first solid foods were potato chips and a grilled cheese sandwich.

In September 2012, the doctor removed the tube, put a bandage over it, and said it would heal in six weeks. If it didn't heal on its own, it would require surgical closure. The doctor seemed so confident that it would close on its own…

…instead, I dealt with this for six agonizing weeks:

Finally, the doctor gave up on it closing on its own. However, her skin integrity was so poor that surgical closure now had a slim chance of success. I had to get her skin healthy again before they could do the closure. I did eventually get her skin to heal enough for the operation, and it was a quick and easy closure. With that, Anja officially closed the g-tube chapter of her life.

Anja was 3 when she came off the ventilator, the oxygen, and no longer needed the g-tube. The next “thing” to deal with was her feet. Although she had undergone some casting previously, she still required a surgery. She was casted (in the full thigh-to-toe casts) for six long weeks to prepare for the surgery. Then, it was finally time. The doctor removed a small bone in each foot so that he could make room to pull down the talus bones into a better position.

She continued to use her braces and walker, and she was approved for a wheelchair. I think she was around 4 or 5 when she was finally able to walk independently, and to be honest, it wasn’t long after that she was riding a bike and roller skating!

The very last thing to go was the trach. She was 7 when it was removed. I remember the doctor told her to take it out herself, and she did. She pulled it out for the last time with her own hand. There was a small hole in her neck for quite some time, but it eventually closed.

There was a tremendous amount of fear and uncertainty when Anja was born. We had no idea what to expect going forward, but it has been remarkable to watch her development and progression. Initially, she required help from so many different machines just to live. We never knew what to expect day to day. We never knew what was causing her medical issues, we just treated her as they came. She came off the ventilator. She came off the oxygen. Both the g-tube and the trach were removed. Her feet were casted, she had surgery, and soon enough she was walking, something the doctors weren’t sure she would ever do. The “horse-shoe kidneys” turned out to be separated, not attached. Although she was born with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (thickening of the heart muscle) and was monitored by a cardiologist for years, eventually her heart muscle was deemed completely normal and no longer required monitoring. Her physical, fine motor, and speech caught up and she no longer needed those therapies. Over time, issue after issue simply disappeared.

Anyone meeting Anja today might observe that she has an irregular gait, a sort of light limp resulting from both the dislocated hips and the foot deformity, and they might notice the scar on her neck from the trach. Beyond these, there are no real indications of all the challenges she has faced and what she has overcome. Today, as I write this, Anja is a very normal 15-year-old girl. She does fine in school, is quite a bookworm, plays the piano beautifully, and is a tremendous help to me around the house with chores and her younger siblings. Her constant chatter would never suggest that there was a time when she couldn't speak and communicated solely through sign language for a few years. She wants to join the religious life and become a nun.

What a beautiful miracle of God! Thank you for sharing this incredible story of your daughter. Your family is so beautiful and I am so glad that God has put you in my path. Your writings touch my heart so deeply and I feel each story in my soul. You are a such a gift from God. Thank you for your faith and always sharing ways to be a true child of God. ♥️

Wow.

This was one long, interesting and emotional read.

Thank you for sharing your story, on IG and now here.

I can only imagine all the strength and grace it must have taken. God has indeed blessed you and your family and Anja herself. Very inspiring indeed.